Quick List Info

Dates Open - 1936 Season: June 6 to November 29, 1936. Open 177 days.

1937 Season: June 12 to October 31, 1937. Open 142 days.

Attendance - 1936 - 6,353,827 Total Attendance.

1937 - 2,384,830 (Unknown whether paid or total attendance.)

International Participants - 1936 - 5. 1937 - 20.

Total Cost - $6,193,086.86 Expo Authority. Estimated $25 million total, including participants. Likely also included city and state funding.

Site Acreage - 174.4 acres.

Sanction and Type - Unsanctioned by the Bureau of International Exhibitions during the first decade of the Bureau. Suggests a recognized event of Special theme such as those held on the 2-3 year or 7-8 year of the decade in today's BIE terms despite acreage above the current BIE limits for that style of expo. Despite minimal international participation in the first year, a House Joint Resolution 293, asked for $3 million, authorized the president to invite foreign participation in the Texas Centennial Exposition, and created the United States Texas Cententennial Commission and U.S. Commissioner-General for expo. President Roosevelt visited the fair.

Ticket Cost - General admission was 50 cents adults, 25 cents children under 12.

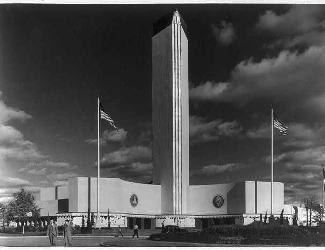

Photo top center: Postcard of the Dallas 1936-7 Texas Centennial Exhibition, the Federal Building at Night, 1936, Original source unknown. Courtesy Pinterest. Column Top: Texas Centennial Souvenir Book, 1936, likely Expo Authority. Courtesy Pinterest. Column Bottom: Electrical and Communications Building, 1936, Original source unknown. Courtesy Pinterest.

Other Histories of World's Fairs to Check Out