-

Timeline - The 1860s

An election would lead to secession and that would lead to Civil War. For four long hard years, over 700,000 citizens of the United States of America would perish in an attempt to solve the state's rights issues surrounding slavery. They would fight across the nation at battlefields such as Gettysburg and Vicksburg with the Confederacy finally losing the battle due to attrition and bold decisions by Abraham Lincoln to emancipate the people enslaved. It was a decade that saw the binding together of a nation that looked as if it would forever be two, and that possibility existed if not for the leadership and bravery of all involved.

More 1800s

-

To the 1800s

-

To the 1810s

-

To the 1820s

-

To the 1830s

-

To the 1840s

-

To the 1850s

-

To the 1860s

-

To the 1870s

-

To the 1880s

-

To the 1890s

-

Back to Index

Civil War

Battle Timeline

Timeline History

Now in easy to search digital format for your Kindle, Nook, or pdf format. Also comes in paperback, too.

ABH Travel Tip

National Park Service sites are made available for your enjoyment of the history and recreation opportunities there. Please take time to keep your parks clean and respect the historic treasures there.

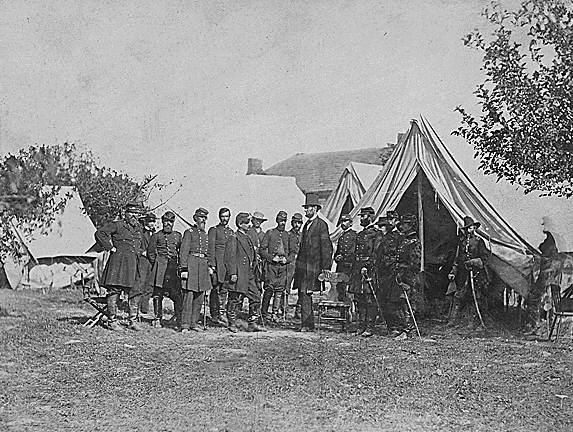

Photo above: President Lincoln and his generals at Antietam after the battle. Courtesy National Archives.

Sponsor this page. Your banner or text ad can fill the space above.

Click here to Sponsor the page and how to reserve your ad.

-

Timeline

1860 - Detail

February 22, 1860 - Twenty thousand New England shoeworkers strike and subsequently win higher wages.

It was 1860, and the brew of Civil War was starting to boil in Kansas and Virginia, but in New England, it was apparent, that the wages that workers had been given, and the profits that the factory workers were making, well, the gap was becoming too large. Their pay had been cut after the Depresssion of 1857. Within one week of the first strike of three thousand workers in Lynn, Massachusetts, deliberately held on Washington's birthday in a town that produced 4.5 million shoes per year, factories in twenty-five shoemaking towns had joined in.

With the Presidential race in full swing between Republican Abraham Lincoln and his four Democratic challengers, Lincoln came out quickly in support of the shoeworkers strike.

"I am glad to see that a system of labor prevails in New England under which laborers can strike when they want to, where they are not obliged to labor whether you pay them or not. I like a system which lets a man quit when he wants to, and wish it might prevail everywhere," Abraham Lincoln, 1860.

Historically, what had started in towns like Lynn, Natick, and other New England towns as a prosperous industry in houses and ten foot shops, had grown by 1834 into a boom with the rail industry shipping thousands of shoes to Boston. Seventy-five percent of the workers in Natick were employed by the shoe making industry. But the financial panic of 1857 had cost many shoeworkers their jobs in those towns, with those men and women encumbering heavy debts. By the time the depression ended, the factory owners held the upper hand, with mechanization by the machines of Singer, patented in 1858, adding to their power. So they offered harsher working conditions, sixteen hour days, and only wages of $3 per week for men and $1 per week for women.

In 1859, the Mechanics Association was formed in Lynn, a union organized by Alonzo Draper, the editor of the New England Mechanic and future Civil War general of the 36th United States Colored Troops, James Dillon, and Napolean Wood, a Methodist minister. They met in early Februrary 1860 to devise a plan and demand higher wages. Their employers refused to meet with them. So, on February 22, 1860, Washington's birthday, the male workers marched to their factories and handed in their tools.

The Strike and Its Outcome

Other towns quickly followed suit. On the same day, shoeworkers in Natick marched through the streets singing Yankee Doodle Dandy with altered words ...

Starvation looks us in the face.

We cannot work so low.

Such prices are a sore disgrace.

Our children ragged go.

The strike leaders urged other shoe towns to organize and strike; Marblehead, Newburyport, Haverhill, Rochester (NH), Dover (NH), Farmington (NH), and Barrington (NH). They went as far as Berwick, Maine and New York City. The newspapers covered the story. They gained supporters each day. By March 8, 1860, women stitchers and binders joined the men in support, marching through the snow to voice their displeasure. On March 18, they held a parade with ten thousand participants from Lynn, Massachusetts and the other shoe towns. It was a peaceful march with alcohol discouraged.

By the second week of the strike, the factory owners were willing to make concessions, but would not recognize the union. On April 10, 1860, the male factory workers of Lynn were offered a 10% raise; one thousand accepted it, even though others were displeased and held out for several more weeks. There would be no raise for the women. Progress for women's rights had not taken the forefront in 1860 New England at all. There were some gains on the Union front, with other towns organizing, and some factories recognizing their right to exist.

Image above: Wood engraving of the march by the Lynn shoemakers in the Shoemaker's Strike, 1860, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. Courtesy Library of Congress. Image below: Bottoming Room of the B.F. Spinney Shoe Factory in Lynn, Massachusetts, 1872, B.F. Spinney and Company. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info source: New England Historical Society; Natick Historical Society; Wikipedia Commons.

History

Photo Bomb

With the Presidential race in full swing between Republican Abraham Lincoln and his four Democratic challengers, Lincoln came out quickly in support of the shoeworkers strike.

"I am glad to see that a system of labor prevails in New England under which laborers can strike when they want to, where they are not obliged to labor whether you pay them or not. I like a system which lets a man quit when he wants to, and wish it might prevail everywhere," Abraham Lincoln, 1860.

Historically, what had started in towns like Lynn, Natick, and other New England towns as a prosperous industry in houses and ten foot shops, had grown by 1834 into a boom with the rail industry shipping thousands of shoes to Boston. Seventy-five percent of the workers in Natick were employed by the shoe making industry. But the financial panic of 1857 had cost many shoeworkers their jobs in those towns, with those men and women encumbering heavy debts. By the time the depression ended, the factory owners held the upper hand, with mechanization by the machines of Singer, patented in 1858, adding to their power. So they offered harsher working conditions, sixteen hour days, and only wages of $3 per week for men and $1 per week for women.

In 1859, the Mechanics Association was formed in Lynn, a union organized by Alonzo Draper, the editor of the New England Mechanic and future Civil War general of the 36th United States Colored Troops, James Dillon, and Napolean Wood, a Methodist minister. They met in early Februrary 1860 to devise a plan and demand higher wages. Their employers refused to meet with them. So, on February 22, 1860, Washington's birthday, the male workers marched to their factories and handed in their tools.

The Strike and Its Outcome

Other towns quickly followed suit. On the same day, shoeworkers in Natick marched through the streets singing Yankee Doodle Dandy with altered words ...

Starvation looks us in the face.

We cannot work so low.

Such prices are a sore disgrace.

Our children ragged go.

The strike leaders urged other shoe towns to organize and strike; Marblehead, Newburyport, Haverhill, Rochester (NH), Dover (NH), Farmington (NH), and Barrington (NH). They went as far as Berwick, Maine and New York City. The newspapers covered the story. They gained supporters each day. By March 8, 1860, women stitchers and binders joined the men in support, marching through the snow to voice their displeasure. On March 18, they held a parade with ten thousand participants from Lynn, Massachusetts and the other shoe towns. It was a peaceful march with alcohol discouraged.

By the second week of the strike, the factory owners were willing to make concessions, but would not recognize the union. On April 10, 1860, the male factory workers of Lynn were offered a 10% raise; one thousand accepted it, even though others were displeased and held out for several more weeks. There would be no raise for the women. Progress for women's rights had not taken the forefront in 1860 New England at all. There were some gains on the Union front, with other towns organizing, and some factories recognizing their right to exist.

Image above: Wood engraving of the march by the Lynn shoemakers in the Shoemaker's Strike, 1860, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. Courtesy Library of Congress. Image below: Bottoming Room of the B.F. Spinney Shoe Factory in Lynn, Massachusetts, 1872, B.F. Spinney and Company. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info source: New England Historical Society; Natick Historical Society; Wikipedia Commons.

History Photo Bomb

About

America's Best History where we take a look at the timeline of American History and the historic sites and national

parks that hold that history within their lands.

Photos courtesy of the Library of Congress, National

Archives, National Park Service, americasbesthistory.com and its licensors.

- Contact Us

- About

- © 2025 Americasbesthistory.com.

Template by w3layouts.