Photo above: Jefferson Memorial. Right: Cuban Embassy in Washington, D.C., 2016. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons.

Sponsor this page for $100 per year. Your banner or text ad can fill the space above.

Click here to Sponsor the page and how to reserve your ad.

-

Timeline

Detail - 2012

May 7, 2012 - The first licenses for cars without drivers is granted in the state of Nevada to Google. Futuristic transportation systems were first introduced in concept during the 1939 World's Fair in New York City in the General Motors exhibit Futurama by Norman Bel Geddes. By September of 2012, three states had passed laws allowing such vehicles; Nevada, California, and Florida.

Yes, soon you will be driving, well, actually passengering, to the supermarket in a driverless car, using their search engine, Google that is, and it will all seem normal just like use of the Internet does today. And it won't be long until that day. In 2005, fifteen engineers working for Google, led by Sebastian Thrun, formerly of Stanford's Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, created Stanley, a robot vehicle that won the DARPA Grand Challenge. The car negotiated a winding course, besting twenty-three other competitors. By 2012, states began to consider how to regulate and license the vehicles, at first for testing purposes. Nevada, in 2011, passed the first law allowing the driverless vehicle, which went into effect on March 1, 2012. Their law required that a driver be in the car, as well as a passenger in the passenger seat. On May 7, Google got the first license for a modified Toyota Prius.

By 2016, technology had outpaced the regulations initially passed by Nevada or the other first states. Driverless cars were now being developed without steering wheels so the need for someone behind the wheel would be moot. All states and the Federal Government began to design new standards and laws surrounding the industry and its potential, involving the testing of such vehicles and any eventual use by the general public. There are estimates the the inclusion of driverless vehicles on United States roads could cost up to five million jobs.

U.S. Department of Transportation Fact Sheet, 2017

FACT SHEET: FEDERAL AUTOMATED VEHICLES POLICY OVERVIEW

The Federal Automated Vehicles Policy sets out a proactive safety approach that will bring lifesaving technologies to the roads safely while providing innovators the space they need to develop new solutions. The Policy is rooted in DOT's view that automated vehicles hold enormous potential benefits for safety, mobility and sustainability. The primary focus of the policy is on highly automated vehicles (HAVs), or those in which the vehicle can take full control of the driving task in at least some circumstances. Portions of the policy also apply to lower levels of automation, including some of the driver-assistance systems already being deployed by automakers today.

Components of the Policy

Vehicle Performance Guidance for Automated Vehicles: The guidance for manufacturers, developers and other organizations outlines a 15 point "Safety Assessment" for the safe design, development, testing and deployment of automated vehicles.

Model State Policy: This section presents a clear distinction between Federal and State responsibilities for regulation of HAVs, and suggests recommended policy areas for states to consider with a goal of generating a consistent national framework for the testing and deployment of highly automated vehicles.

Current Regulatory Tools: This discussion outlines DOT's current regulatory tools that can be used to accelerate the safe development of HAVs, such as interpreting current rules to allow for greater flexibility in design and providing limited exemptions to allow for testing of nontraditional vehicle designs in a more timely fashion.

Modern Regulatory Tools: This discussion identifies potential new regulatory tools and statutory authorities that may aid the safe and efficient deployment of new lifesaving technologies.

Policy Development and Public Comment

The Policy is a product of significant public input, including two public meetings and an open public docket. The Policy will be updated annually to ensure it remains relevant and timely, and will continue to be shaped by public comment, industry feedback and real-world experience. DOT is seeking public comment on the entire policy at www.transportation.gov/AV.

Most of the Policy is effective on the date of its publication. However, certain elements involving data and information collection will be effective upon the completion of a Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA) review and process.

The policy outlines a series of next steps that the agency will take to solicit additional public input and to implement the components. The next steps include public workshops, stakeholder engagement, expert review, work plans to implement Policy components, possible rulemakings, and education efforts.

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety

FACT SHEET: AV POLICY SECTION I: VEHICLE PERFORMANCE

GUIDANCE FOR AUTOMATED VEHICLES

The Vehicle Performance Guidance for Automated Vehicles ("Guidance") outlines best practices for the safe design, development and testing of automated vehicles prior to commercial sale or operation on public roads.

The Guidance includes a 15-Point Safety Assessment to set clear expectations for manufacturers developing and deploying automated vehicle technologies.

For companies, the Guidance describes internal processes and strategies, organizational awareness, record-keeping, testing and validation, engagement with DOT and NHTSA, and improved transparency to support the safe deployment of HAV technology. The industry's adoption and use of the Guidance, which DOT and NHTSA will review annually and update as necessary, will build public confidence and maintain the U.S. lead on these emerging automotive safety technologies.

Application - Systems: The Guidance applies primarily to technologies where the system can do the entire driving task without reliance on the driver to pay continuous attention to the driving environment. Portions also apply to lower levels of automated driving systems.

Vehicles: The Guidance applies to all classes of motor vehicles, including passenger cars, trucks and buses.

Organizations: The Guidance covers any organization testing, operating, and/or deploying automated vehicles, which includes traditional companies (e.g. auto manufacturers, suppliers) and nontraditional companies (e.g. tech companies, startups, fleet operators).

The information generated from these activities will be shared in a way that allows government, industry, and the public to increase their learning and understanding as technology evolves, while protecting legitimate privacy and competitive interests.

15-point Safety Assessment

The 15-point Safety Assessment outlines objectives on how to achieve a robust design. It allows for varied methodologies as long as the objective is met. The Guidance asks manufacturers and other entities to document how they are meeting each topic area in the guidance. The issues include:

Operational Design Domain: How and where the HAV is supposed to function and operate;

Object and Event Detection and Response: Perception and response functionality of the HAV system;

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety

Fall Back (Minimal Risk Condition): Response and robustness of the HAV upon system failure;

Validation Methods: Testing, validation, and verification of an HAV system;

Registration and Certification: Registration and certification to NHTSA of an HAV system;

Data Recording and Sharing: HAV system data recording for information sharing, knowledge building and for crash reconstruction purposes;

Post-Crash Behavior: Process for how an HAV should perform after a crash and how automation functions can be restored;

Privacy: Privacy considerations and protections for users;

System Safety: Engineering safety practices to support reasonable system safety;

Vehicle Cybersecurity: Approaches to guard against vehicle hacking risks;

Human Machine Interface: Approaches for communicating information to the driver, occupant and other road users;

Crashworthiness: Protection of occupants in crash situations;

Consumer Education and Training: Education and training requirements for users of HAVs;

Ethical Considerations: How vehicles are programmed to address conflict dilemmas on the road; and

Federal, State and Local Laws: How vehicles are programmed to comply with all applicable traffic laws.

Portions of the Guidance also apply to developers of lower level automated systems that are designed to assist the driver but not take the over the driving task. The Guidance outlines a Safety Assessment for these systems as well.

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety - FACT SHEET: AV POLICY SECTION II: MODEL STATE POLICY - State governments play an important role in facilitating HAVs, ensuring they are safely deployed and promoting their life-saving benefits. The Model State Policy confirms that States retain their traditional responsibilities for vehicle licensing and registration, traffic laws and enforcement, and motor vehicle insurance and liability regimes while outlining the Federal role for HAVs. The Model State Policy supports the establishment of a consistent national framework of laws and policy to govern automated vehicles.

Division of Federal and State Responsibilities. Federal responsibilities include:

Setting safety standards for new motor vehicles and motor vehicle equipment;

Enforcing compliance with the safety standards;

Investigating and managing the recall and remedy of non-ompliances and safety-related motor vehicle defects on a nationwide basis;

Communicating with and educating the public about motor vehicle safety issues; and

When necessary, issuing guidance to achieve national safety goals

State responsibilities include: Licensing (human) drivers and registering motor vehicles in their jurisdictions; Enacting and enforcing traffic laws and regulations; Conducting safety inspections, when States choose to do so; and Regulating motor vehicle insurance and liability.

The Model State Policy - The Model State Policy is intended for States that wish to regulate testing, deployment, and operation of HAVs. The model framework addresses State regulation of the procedures and requirements for granting permission to vehicle manufacturers and owners to test and operate vehicles within a State.

Model framework areas covered include: Administrative structure and processes that States can set up to administer requirements regarding the use of public roads for HAV testing and deployment in their States; Application by manufacturers or other entities to test HAVs on public roads; Jurisdictional permission to test;

Testing by the manufacturer or other entities; Drivers of deployed vehicles; Registration and titling of deployed vehicles; Law enforcement considerations; and Liability and insurance.

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety - FACT SHEET: AV POLICY SECTION III: CURRENT REGULATORY TOOLS

This section summarizes how existing regulatory tools will be used to promote the safe development and deployment of automated vehicles, including interpretations, exemptions, notice-and-comment rulemaking, and defects and enforcement authority. NHTSA (the "Agency") has streamlined its review process and is committing to expediting simple HAV-related interpretations and exemption requests.

Letters of Interpretation - The Agency can use letters of interpretations to explain how existing law applies to specific motor vehicle equipment. Interpretation letters describe the Agency's view of the meaning and application of an existing statute or regulation. They can better explain the meaning of a regulation, statute, or overall legal framework and provide clarity for regulated entities and the public.

An interpretation may not make a substantive change to the meaning of a statute or regulation or to their clear provisions and requirements. In particular, an interpretation may not adopt a new position that is irreconcilable with or repudiates existing statutory or regulatory provisions.

Historically, interpretation letters have taken several months to several years for NHTSA to issue, but the Agency has committed to expediting simple interpretation requests regarding HAVs to provide responses in 60 days.

Exemptions from Existing Standards - The Agency has authority to provide limited exemptions from existing standards to accommodate alternate vehicle designs. Manufacturers can apply for exemptions that may allow for the deployment of vehicle test fleets with significantly different vehicle designs that would otherwise not be compliant with standards.

Agency rulings on exemptions have historically taken several months to several years. The Agency has committed to expediting simple exemption requests regarding HAVs to provide responses within six months.

Rulemakings - Notice-and-comment rulemaking is the tool the Agency uses to adopt new standards, modify existing standards, or repeal an existing standard. If a party wishes to avoid compliance with a standard for longer than the allowed time period for exemptions, or for a greater number of vehicles than the allowed number for exemptions, or has a motor vehicle or equipment design substantially different from anything currently on the road that compliance with standards may be very difficult or complicated (or new standards may be needed), a petition for rulemaking may be the best path forward.

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety - Enforcement Authority NHTSA has broad enforcement authority under existing statutes and regulations to address existing and emerging automotive technologies. Part of the agency's mission is to protect against unreasonable risks of harm that may occur because of the design, construction, or performance of a motor vehicle or motor vehicle equipment, and to mitigate risks of harm. As described in the accompanying Enforcement Bulletin, NHTSA's existing authority and responsibility covers defects that create unreasonable risks to safety that may arise in connection with HAVs.

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety - FACT SHEET: AV POLICY SECTION IV: MODERN REGULATORY TOOLS

This section identifies potential new tools, authorities and resources that could aid the safe deployment of new automated technologies by enabling DOT to be more nimble and flexible. Some of the identified tools could be created under current law while others would require Congressional action.

Today's governing statutes and regulations were developed before HAVs were even a remote notion. Current authorities and tools alone may be insufficient to ensure that HAVs are introduced safely, and to realize the full safety promise of new technologies. This challenge requires DOT and NHTSA to examine whether the ways in which the Agency has addressed safety for the last several decades should be expanded to realize the safety potential of HAVs over the decades to come.

Considered New Authorities - Safety Assurance: Methods and tools for vehicle manufacturers and other organizations to provide pre-market testing, data and analyses to DOT to demonstrate that organization's design, manufacturing and testing processes apply NHTSA's vehicle performance guidance.

Pre-Market Approval: Pre-market approval authority, in which the government inspects and affirmatively approves new technologies, would be a departure from NHTSA's current self-certification system. The merits and challenges of implementing some form of a pre-market approval are discussed.

Cease and Desist: Authority to require manufacturers to take immediate action to mitigate safety risks that are so serious and immediate that they constitute "imminent hazards."

Expanded Exemptions: Raising the cap on the number of vehicles subject to exemption and/or the length of time of exemptions, to facilitate the safe testing and introduction of HAVs.

Post-sale Regulation of Software Changes: This authority would clarify the Agency's ability to regulate post-sale software changes in HAVs.

Considered New Tools - Variable Test Procedures: Expand vehicle testing methods to create test environments more representative of real-world environments. Functional and System Safety: Make mandatory the 15-point Safety Assessment envisioned in the Vehicle Performance Guidance for Automated Vehicles.

Regular Reviews: Regular reviews of standards and testing protocols to keep current with the development of technology.

Additional Recordkeeping and Reporting: Require additional reporting about HAV testing and deployment.

Enhanced Data Collection: Enhance data recorders and greater reporting requirements about the performance of HAVs.

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety - Considered New Resources - Network of Experts: Establish a network of experts to broaden the NHTSA's existing expertise and knowledge.

Special Hiring Tools: Special hiring tools - including direct hiring authority, term appointments, and greater compensation flexibility-to hire qualified applicants with specialized skills.

Where the Driverless Car Industry is Now

In 2015, Google tested a fully functioning driverless car, with no steering wheel or pedal, on a public road in Texas for the first time. In May of 2016, one hundred text mini-vans were ordered by Google. These cars cost approximately $150,000, including the LIDAR system at $70,000, a laser guided detection system that allows the car to know its surroundings. Testing by June 2016 had completed 1.7 million miles. Google now operates its driverless car division under the subsidiary Waymo.

Testing continues on driverless vehicles with some predictions of 2020 that the technology could reach the point of partial implementation.

Futurama and the Prediction

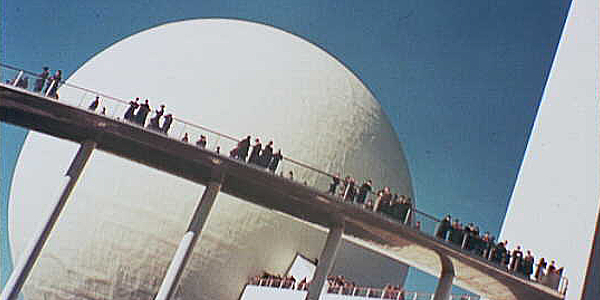

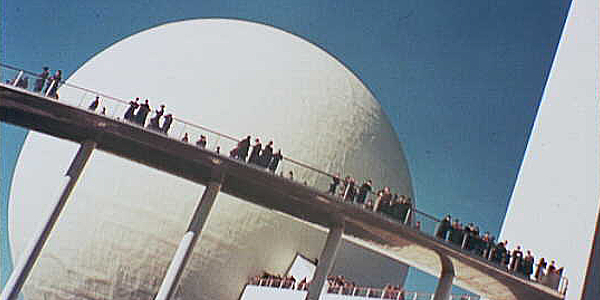

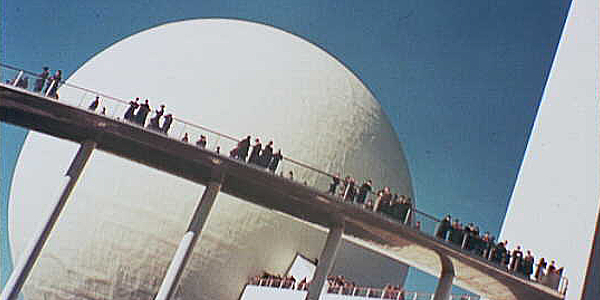

At the New York World's Fair of 1939, as World War II was on the brew, industrial designers and visionaries began to imagine what the world what might look like in the future. In the Transportation Zone, the exhibit, Futurama, built for General Motors by one of those designers, Norman Bel Geddes, father of Miss Ellie from the 1980 television series Dallas, envisioned the interstate highway system with its looping interchanges. And while he did not show a driverless car, the passengers of the journey to the exhibit were transported in driverless chairs above the diorama that included fifty thousand vehicles and five hundred thousand homes. In Henry Dreyfuss' exhibit inside the Perisphere of the Trylon and Perisphere was another exhibit of similar theme, Democracity, which envisioned a utopian city of tomorrow. Somehow, the visions seen in those two exhibits had led us to the driverless cars of today, and tomorrow. Hey, we're still using the same vision for the highway system almost eighty years later.

Photo above: Driverless car being tested in 2011, 2011. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons. Photo below: Incline view of the Trylon and Perisphere, 1939, Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info source: U.S. Transportation Department; Cyberlaw, Stanford.edu; Wikipedia Commons.

History Photo Bomb

By 2016, technology had outpaced the regulations initially passed by Nevada or the other first states. Driverless cars were now being developed without steering wheels so the need for someone behind the wheel would be moot. All states and the Federal Government began to design new standards and laws surrounding the industry and its potential, involving the testing of such vehicles and any eventual use by the general public. There are estimates the the inclusion of driverless vehicles on United States roads could cost up to five million jobs.

U.S. Department of Transportation Fact Sheet, 2017

FACT SHEET: FEDERAL AUTOMATED VEHICLES POLICY OVERVIEW

The Federal Automated Vehicles Policy sets out a proactive safety approach that will bring lifesaving technologies to the roads safely while providing innovators the space they need to develop new solutions. The Policy is rooted in DOT's view that automated vehicles hold enormous potential benefits for safety, mobility and sustainability. The primary focus of the policy is on highly automated vehicles (HAVs), or those in which the vehicle can take full control of the driving task in at least some circumstances. Portions of the policy also apply to lower levels of automation, including some of the driver-assistance systems already being deployed by automakers today.

Components of the Policy

Vehicle Performance Guidance for Automated Vehicles: The guidance for manufacturers, developers and other organizations outlines a 15 point "Safety Assessment" for the safe design, development, testing and deployment of automated vehicles.

Model State Policy: This section presents a clear distinction between Federal and State responsibilities for regulation of HAVs, and suggests recommended policy areas for states to consider with a goal of generating a consistent national framework for the testing and deployment of highly automated vehicles.

Current Regulatory Tools: This discussion outlines DOT's current regulatory tools that can be used to accelerate the safe development of HAVs, such as interpreting current rules to allow for greater flexibility in design and providing limited exemptions to allow for testing of nontraditional vehicle designs in a more timely fashion.

Modern Regulatory Tools: This discussion identifies potential new regulatory tools and statutory authorities that may aid the safe and efficient deployment of new lifesaving technologies.

Policy Development and Public Comment

The Policy is a product of significant public input, including two public meetings and an open public docket. The Policy will be updated annually to ensure it remains relevant and timely, and will continue to be shaped by public comment, industry feedback and real-world experience. DOT is seeking public comment on the entire policy at www.transportation.gov/AV.

Most of the Policy is effective on the date of its publication. However, certain elements involving data and information collection will be effective upon the completion of a Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA) review and process.

The policy outlines a series of next steps that the agency will take to solicit additional public input and to implement the components. The next steps include public workshops, stakeholder engagement, expert review, work plans to implement Policy components, possible rulemakings, and education efforts.

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety

FACT SHEET: AV POLICY SECTION I: VEHICLE PERFORMANCE

GUIDANCE FOR AUTOMATED VEHICLES

The Vehicle Performance Guidance for Automated Vehicles ("Guidance") outlines best practices for the safe design, development and testing of automated vehicles prior to commercial sale or operation on public roads.

The Guidance includes a 15-Point Safety Assessment to set clear expectations for manufacturers developing and deploying automated vehicle technologies.

For companies, the Guidance describes internal processes and strategies, organizational awareness, record-keeping, testing and validation, engagement with DOT and NHTSA, and improved transparency to support the safe deployment of HAV technology. The industry's adoption and use of the Guidance, which DOT and NHTSA will review annually and update as necessary, will build public confidence and maintain the U.S. lead on these emerging automotive safety technologies.

Application - Systems: The Guidance applies primarily to technologies where the system can do the entire driving task without reliance on the driver to pay continuous attention to the driving environment. Portions also apply to lower levels of automated driving systems.

Vehicles: The Guidance applies to all classes of motor vehicles, including passenger cars, trucks and buses.

Organizations: The Guidance covers any organization testing, operating, and/or deploying automated vehicles, which includes traditional companies (e.g. auto manufacturers, suppliers) and nontraditional companies (e.g. tech companies, startups, fleet operators).

The information generated from these activities will be shared in a way that allows government, industry, and the public to increase their learning and understanding as technology evolves, while protecting legitimate privacy and competitive interests.

15-point Safety Assessment

The 15-point Safety Assessment outlines objectives on how to achieve a robust design. It allows for varied methodologies as long as the objective is met. The Guidance asks manufacturers and other entities to document how they are meeting each topic area in the guidance. The issues include:

Operational Design Domain: How and where the HAV is supposed to function and operate;

Object and Event Detection and Response: Perception and response functionality of the HAV system;

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety

Fall Back (Minimal Risk Condition): Response and robustness of the HAV upon system failure;

Validation Methods: Testing, validation, and verification of an HAV system;

Registration and Certification: Registration and certification to NHTSA of an HAV system;

Data Recording and Sharing: HAV system data recording for information sharing, knowledge building and for crash reconstruction purposes;

Post-Crash Behavior: Process for how an HAV should perform after a crash and how automation functions can be restored;

Privacy: Privacy considerations and protections for users;

System Safety: Engineering safety practices to support reasonable system safety;

Vehicle Cybersecurity: Approaches to guard against vehicle hacking risks;

Human Machine Interface: Approaches for communicating information to the driver, occupant and other road users;

Crashworthiness: Protection of occupants in crash situations;

Consumer Education and Training: Education and training requirements for users of HAVs;

Ethical Considerations: How vehicles are programmed to address conflict dilemmas on the road; and

Federal, State and Local Laws: How vehicles are programmed to comply with all applicable traffic laws.

Portions of the Guidance also apply to developers of lower level automated systems that are designed to assist the driver but not take the over the driving task. The Guidance outlines a Safety Assessment for these systems as well.

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety - FACT SHEET: AV POLICY SECTION II: MODEL STATE POLICY - State governments play an important role in facilitating HAVs, ensuring they are safely deployed and promoting their life-saving benefits. The Model State Policy confirms that States retain their traditional responsibilities for vehicle licensing and registration, traffic laws and enforcement, and motor vehicle insurance and liability regimes while outlining the Federal role for HAVs. The Model State Policy supports the establishment of a consistent national framework of laws and policy to govern automated vehicles.

Division of Federal and State Responsibilities. Federal responsibilities include:

Setting safety standards for new motor vehicles and motor vehicle equipment;

Enforcing compliance with the safety standards;

Investigating and managing the recall and remedy of non-ompliances and safety-related motor vehicle defects on a nationwide basis;

Communicating with and educating the public about motor vehicle safety issues; and

When necessary, issuing guidance to achieve national safety goals

State responsibilities include: Licensing (human) drivers and registering motor vehicles in their jurisdictions; Enacting and enforcing traffic laws and regulations; Conducting safety inspections, when States choose to do so; and Regulating motor vehicle insurance and liability.

The Model State Policy - The Model State Policy is intended for States that wish to regulate testing, deployment, and operation of HAVs. The model framework addresses State regulation of the procedures and requirements for granting permission to vehicle manufacturers and owners to test and operate vehicles within a State.

Model framework areas covered include: Administrative structure and processes that States can set up to administer requirements regarding the use of public roads for HAV testing and deployment in their States; Application by manufacturers or other entities to test HAVs on public roads; Jurisdictional permission to test;

Testing by the manufacturer or other entities; Drivers of deployed vehicles; Registration and titling of deployed vehicles; Law enforcement considerations; and Liability and insurance.

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety - FACT SHEET: AV POLICY SECTION III: CURRENT REGULATORY TOOLS

This section summarizes how existing regulatory tools will be used to promote the safe development and deployment of automated vehicles, including interpretations, exemptions, notice-and-comment rulemaking, and defects and enforcement authority. NHTSA (the "Agency") has streamlined its review process and is committing to expediting simple HAV-related interpretations and exemption requests.

Letters of Interpretation - The Agency can use letters of interpretations to explain how existing law applies to specific motor vehicle equipment. Interpretation letters describe the Agency's view of the meaning and application of an existing statute or regulation. They can better explain the meaning of a regulation, statute, or overall legal framework and provide clarity for regulated entities and the public.

An interpretation may not make a substantive change to the meaning of a statute or regulation or to their clear provisions and requirements. In particular, an interpretation may not adopt a new position that is irreconcilable with or repudiates existing statutory or regulatory provisions.

Historically, interpretation letters have taken several months to several years for NHTSA to issue, but the Agency has committed to expediting simple interpretation requests regarding HAVs to provide responses in 60 days.

Exemptions from Existing Standards - The Agency has authority to provide limited exemptions from existing standards to accommodate alternate vehicle designs. Manufacturers can apply for exemptions that may allow for the deployment of vehicle test fleets with significantly different vehicle designs that would otherwise not be compliant with standards.

Agency rulings on exemptions have historically taken several months to several years. The Agency has committed to expediting simple exemption requests regarding HAVs to provide responses within six months.

Rulemakings - Notice-and-comment rulemaking is the tool the Agency uses to adopt new standards, modify existing standards, or repeal an existing standard. If a party wishes to avoid compliance with a standard for longer than the allowed time period for exemptions, or for a greater number of vehicles than the allowed number for exemptions, or has a motor vehicle or equipment design substantially different from anything currently on the road that compliance with standards may be very difficult or complicated (or new standards may be needed), a petition for rulemaking may be the best path forward.

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety - Enforcement Authority NHTSA has broad enforcement authority under existing statutes and regulations to address existing and emerging automotive technologies. Part of the agency's mission is to protect against unreasonable risks of harm that may occur because of the design, construction, or performance of a motor vehicle or motor vehicle equipment, and to mitigate risks of harm. As described in the accompanying Enforcement Bulletin, NHTSA's existing authority and responsibility covers defects that create unreasonable risks to safety that may arise in connection with HAVs.

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety - FACT SHEET: AV POLICY SECTION IV: MODERN REGULATORY TOOLS

This section identifies potential new tools, authorities and resources that could aid the safe deployment of new automated technologies by enabling DOT to be more nimble and flexible. Some of the identified tools could be created under current law while others would require Congressional action.

Today's governing statutes and regulations were developed before HAVs were even a remote notion. Current authorities and tools alone may be insufficient to ensure that HAVs are introduced safely, and to realize the full safety promise of new technologies. This challenge requires DOT and NHTSA to examine whether the ways in which the Agency has addressed safety for the last several decades should be expanded to realize the safety potential of HAVs over the decades to come.

Considered New Authorities - Safety Assurance: Methods and tools for vehicle manufacturers and other organizations to provide pre-market testing, data and analyses to DOT to demonstrate that organization's design, manufacturing and testing processes apply NHTSA's vehicle performance guidance.

Pre-Market Approval: Pre-market approval authority, in which the government inspects and affirmatively approves new technologies, would be a departure from NHTSA's current self-certification system. The merits and challenges of implementing some form of a pre-market approval are discussed.

Cease and Desist: Authority to require manufacturers to take immediate action to mitigate safety risks that are so serious and immediate that they constitute "imminent hazards."

Expanded Exemptions: Raising the cap on the number of vehicles subject to exemption and/or the length of time of exemptions, to facilitate the safe testing and introduction of HAVs.

Post-sale Regulation of Software Changes: This authority would clarify the Agency's ability to regulate post-sale software changes in HAVs.

Considered New Tools - Variable Test Procedures: Expand vehicle testing methods to create test environments more representative of real-world environments. Functional and System Safety: Make mandatory the 15-point Safety Assessment envisioned in the Vehicle Performance Guidance for Automated Vehicles.

Regular Reviews: Regular reviews of standards and testing protocols to keep current with the development of technology.

Additional Recordkeeping and Reporting: Require additional reporting about HAV testing and deployment.

Enhanced Data Collection: Enhance data recorders and greater reporting requirements about the performance of HAVs.

Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety - Considered New Resources - Network of Experts: Establish a network of experts to broaden the NHTSA's existing expertise and knowledge.

Special Hiring Tools: Special hiring tools - including direct hiring authority, term appointments, and greater compensation flexibility-to hire qualified applicants with specialized skills.

Where the Driverless Car Industry is Now

In 2015, Google tested a fully functioning driverless car, with no steering wheel or pedal, on a public road in Texas for the first time. In May of 2016, one hundred text mini-vans were ordered by Google. These cars cost approximately $150,000, including the LIDAR system at $70,000, a laser guided detection system that allows the car to know its surroundings. Testing by June 2016 had completed 1.7 million miles. Google now operates its driverless car division under the subsidiary Waymo.

Testing continues on driverless vehicles with some predictions of 2020 that the technology could reach the point of partial implementation.

Futurama and the Prediction

At the New York World's Fair of 1939, as World War II was on the brew, industrial designers and visionaries began to imagine what the world what might look like in the future. In the Transportation Zone, the exhibit, Futurama, built for General Motors by one of those designers, Norman Bel Geddes, father of Miss Ellie from the 1980 television series Dallas, envisioned the interstate highway system with its looping interchanges. And while he did not show a driverless car, the passengers of the journey to the exhibit were transported in driverless chairs above the diorama that included fifty thousand vehicles and five hundred thousand homes. In Henry Dreyfuss' exhibit inside the Perisphere of the Trylon and Perisphere was another exhibit of similar theme, Democracity, which envisioned a utopian city of tomorrow. Somehow, the visions seen in those two exhibits had led us to the driverless cars of today, and tomorrow. Hey, we're still using the same vision for the highway system almost eighty years later.

Photo above: Driverless car being tested in 2011, 2011. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons. Photo below: Incline view of the Trylon and Perisphere, 1939, Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info source: U.S. Transportation Department; Cyberlaw, Stanford.edu; Wikipedia Commons.

History Photo Bomb

Photo above: Driverless car being tested in 2011, 2011. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons. Photo below: Incline view of the Trylon and Perisphere, 1939, Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info source: U.S. Transportation Department; Cyberlaw, Stanford.edu; Wikipedia Commons.