Sponsor this page. Your banner or text ad can fill the space above.

Click here to Sponsor the page and how to reserve your ad.

-

Timeline

1825 Detail

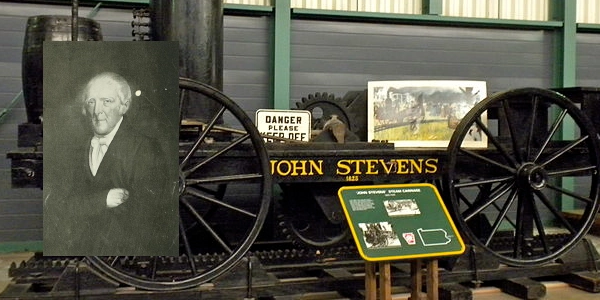

1825 - The first experimental steam locomotive is built and operated by John Stevens, of Hoboken, New Jersey, to prove the viability of railroads. It would be given its first public test in May 1826.

John Stevens had already had a remarkable career by 1825. He had been a main advocate for the patent law which passed Congress on April 10, 1790, one of the first acts of business by the United States Congress after the American Revolution ended. In that war for American independence, Stevens had been a captain, then rose to the rank of colonel, as well as the Treasurer of New Jersey. After it, he used the patent system to gain one of the first patents in 1791, yes, for a steam engine. By 1825, Stevens was on his Stevens Villa estate in Hoboken, New Jersey, constructing the first experimental steam locomotive engine as well as a track to test it. It had been a natural progression for Stevens to go from establishing patent law to the machines he would patent.

There had been many accomplishments in the interim years. In 1802, Stevens had constructed a screw-driven steamboat; in 1806, a sidewheeling steamboat he would successfully traverse the ocean from Hoboken to Philadelphia three years later. By 1811, he had established a steam powered ferry service from New York City to Hoboken, and four years later, on February 6, 1815, Stevens acquired the first charter for a railroad, the New Jersey Railroad, which allowed him the rights to build from Trenton to New Brunswick, from the River Delaware to the River Raritan. That charter and railroad were never built, as it could not attract enough capital through investors. In 1823, the Pennsyvlania Railroad passed a law for a new railroad to be built by John Stevens from Philadelphia to Columbia. It was not built either, unable to gain enough investors.

However, the need to bind a large nation together still existed, although whether that be by rail, which had only been widely attempted in the mining industry in England, or by extending canals was in question. During the decade between that first charter, unfulfilled, and the date of his test, the debate between the speed and cost of building railroads versus canals was ongoing, both in industrial and political society on both sides of the Atlantic. New York politican DeWitt Clinton, a former opponent to the ideas of Stevens, now suggested that an experiment was needed to prove his claims. Newspaper letters to the editor were written on the subject, debating the merits. Yes, that's what folks discussed back then.

"... By one of those extracts it appears that the estimated cost of a canal between two points mentioned, was 650,000 pounds sterling - whilst that of a Rail Way between the same two points was but 149,206 pounds. The calculated cost of the canal, then, was more than treble that of a Rail Way.

It has before been stated that the utmost speed that can be admitted on a canal is three miles per hour - it however appears by the extracts above mentioned, that heavy loaded wagons may, on a Rail Way, be drawn at a rate of 6 miles per hour; and by means of a locomotive engine, stage coaches, or wagons for the conveyance of light goods, may be drawn at a rate of 12 miles an hour. This fully corroborates what has been previously stated in the Watchman - and exhibits a gain in speed over a canal, of from 50 to 400 per cent, ..." To the Editors of the Watchman, American Watchman and Delaware Advertiser, September 23, 1825.

So what about that steam locomotive of that 1825 date? On his Hoboken estate, John Stevens built a circular track, one half mile long, and steam engine, sixteen feet long by four feet two and one half inches high, in 1825, to show that steam powered rail was possible, could climb grades, and thereby be worthy of investment. Although the New Jersey Railroad had failed to achieve capital, Stevens wanted to make certain that a second venture would gain subsequent investment. His test was designed to convince the Pennsylvania Society of Internal Improvement that his system could be used on the Pennsylvania Railroad.

"Rail Roads have nowhere yet been made, on this side of the Atlantic. Let the experiment be fairly tried," John Stevens.

The first public test was not ready in 1825, it would have to wait until May 1826. Passengers climbed aboard the train. It circled the lower ground of the estate at six miles per hour. Over the next several months, Stevens increased its load, taking up to six passengers on their rides, with speeds that approached and sometimes exceeded twelve miles per hour. The representatives of the Pennsylvania Society were impressed. He would continue experimenting and testing his locomotive on various track layouts through 1829, but saw even loftier goals.

"I can see nothing to hinder a steam engine from moving with a velocity of 100 miles per hour. In practice, it may not be advisable to exceed 20 or 30 miles per hour, but I should not be surprised at seeing carriages propelled to 40 or 50," John Stevens.

Although that locomotive was never put into commercial service, it paved the way for that new venture, the Camden and Amboy Railroad. With the testing done between 1825 and 1829, that venture raised one million dollars in subscriptions in ten minutes. The Camden and Amboy Railroad would be chartered on February 4, 1830 and begin construction later that year. Robert Stevens, his son, would become that railroad's President over the next two decades; Edwin Stevens, one of his other sons, would be its Treasurer.

John Stevens and Robert Fulton

Once the American Revolution had wrestled the colonies from its British counterparts, John Stevens turned his attention to commercial ventures, including land surveys and transportation, with a complete fascination with the possibility of steam. In 1788, he began to experiment with steam boilers for use in the maritime industry. Yes, boats. In many ways, he was competing against the work of Robert Fulton, who, with his boat Clermont, would beat Stevens to the punch when, on August 17, 1807, he made the first practical steamboat journey from New York City to Albany.

Stevens would continue that work, however, constructing the first major American built steamboat, the Phoenix, which, in 1809, began to transport freight and passengers on the Atlantic Ocean between New York and New Jersey. His advocacy for using high boilder pressure, reaching 100 psi, surpassed earlier studies by James Watt who thought 3 psi was the practical limit. His ideas were thought impractical, argued against by Fulton and other collegues.

"Heard John Stevens' latest? He's making a damned fool of himself over steam waggons!," 1812.

Despite these protestations, as witnessed by the 1815 charter of the New Jersey Railroad and the subsequent experiments of 1825 to 1829, Colonel Stevens would eventually succeed over his critics. He would prove the viability of the steam locomotive with his experiments on his Hoboken estate, with his sons taking the Camden and Amboy Railroad through its first decades of steam locomotive

travel, even if it was not with their father's original locomotive design.

Image above: Montage (inset) Colonel John Stevens, 1912, George Iles, Leading American Inventors; (background) Replica of the John Stevens Steam Locomotive on display at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania, 2010. Both courtesy Wikipedia Commons. Image below: Engraving of John Stevens home, Stevens Villa, Hoboken, New Jersey, 1808, William Russell Birch. Courtesy Library of Congress. Source Info: Hoboken Historical Museum; "John Stevens: The Man and the Machine," James Alexander, Jr.; American Watchman and Delaware Advertiser; Library of Congress, Chronicling America; "John Stevens, An American Record," 1928, Archibald Douglas Turnball; Wikipedia Commons.

History

Photo Bomb