Sponsor this page. Your banner or text ad can fill the space above.

Click here to Sponsor the page and how to reserve your ad.

-

Timeline

1816 - Detail

June 21, 1816 - The entire "Year without a Summer" occurs in the United States, the northern hemisphere, and around the world due to global cooling caused by the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815.

Article by Jason Donovan

Along the Ring of Fire in the Pacific Ocean, there are numerous volcanos whose

eruptions are inconsequential to most people’s lives. Then there are the few and far

between that change the lives of all on earth to some extent. The latter type of eruption

occurred on 10 April 1815, when Mount Tambora created the most enormous

explosion in recorded history. Its effects on the world would become the summer that

wasn’t, the year that was 1816.

Thousands of years of inactivity ended after three years of tremors and smoke.

Mount Tambora on the island of Sumbawa in Indonesia awoke from its years of

slumber with the largest explosion ever recorded within the course of human history. A

minor eruption occurred on the 5th. The sounds of these explosions were heard for

hundreds of miles around. Many British colonial government officials administrating the

islands stated that, at first, they thought the explosions they heard were cannon shots

or thunderclaps. In reality, the mountain was blowing itself apart. The eruption caused

over 35 cubic miles of lava, ash, and mountain to be ejected into the stratosphere. As

the eruption proceeded, the enormous columns of lava, ash, and ejected material

eventually collapsed, bringing on pyroclastic flows. Pyroclastic flows are fast-moving

flows of material and superheated gases that move at “200 meters per second” and at

“temperatures 200-700 degrees Celsius (390-1300 degrees Fahrenheit). The terra firma

and the air were only two of the three aspects of the immediate aftermath of the

eruption; the last was the water. A tsunami approximately 12 feet in height hit the

surrounding area. The mountain literally blew itself apart, nearly 1500 meters of its

height disappearing, most likely into that before-mentioned stratosphere. These were

just the immediate effects of the blast. Most of the remaining effects would develop

over the next few years. The climate of the time was already colder than average,

known as The Little Ice Age.

Little Ice Age

The weather of 1816 was only made worse by its inclusion in the timeframe

known as “The Little Ice Age.” The period covered by this name stretches from the

1400s to 1860. This period experienced colder temperatures, droughts in some areas,

and heavy rains in others. The same period in time was that of the “Age of

Exploration.” The climate affected how the colonial powers faired in the new world. The

cold, dry weather made life in the early colonies unbearable and exceedingly deadly

due to the failure of crops and the harsh winters. These settlers had the mistaken idea

that the climate of the new world was the same as that which they left in their home

countries. The newcomers abandoned many attempts, such as Sagadahoc, Maine,

which was abandoned in 1608. The climate of the New World slowed colonization by

decades. The Little Ice Age only served to prime the atmosphere, one eruption

away from the “Year Without A Summer.”

The Year Without a Summer

1816 was the year when the particles that used to be Mount Tambora months

prior finally made their way to the United States, developing the weather

patterns of 1816 and the following few years. The largest reason was the composition

of the ash cloud. A significant component of the cloud was the 60 megatons of sulfur

gas that were expelled into the stratosphere. This composition was a one-two punch.

Where ash blocks the sunlight, the sulfur particles reflect sunlight, thus leaving very

little to reach the ground.

The New England and Mid-Atlantic regions provide a stark case study of the

suffering and death brought on by the changes in the climate. There is a modern-day

example of a large volcanic eruption affecting worldwide climate for at least the

following three years. The 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption released 20 megatons of

sulfuric gas 20 miles into the atmosphere. Pinatubo released a third of the amount of

Tambora and dropped surface temperatures by 1.3 degrees Fahrenheit. In contrast, the

drop in temperature in 1816 was 2-7 degrees Fahrenheit. A drop in temperatures this

severe resulted in each month of the year containing at least one “hard frost.” As

Vermont historian Howard Coffin implies, during his interview with Bob Kinzel on

Vermont Public Radio, there were warm days in the spring by stating that the weather

started to turn around 5 June. During the interview, a caller reads from his “4th great

grandmother’s diary.” The diary covers 1812-1838. The caller states that the diary has

daily entries covering the weather for all of 1816.

She states in its pages, ”fourth day Tuesday cloudy and cold rains night, Wednesday some clear and warm in the afternoon till just night showers and thunder, Thursday very cold, a little snow, some rain in the forenoon snow squalls afterward on the ground was white with snow at night, and freezing cold, seventh day Friday very cold and windy vegetables froze

snow squalls toward night ground covered with snow.”

The caller’s grandmother also discusses her state of mind at the time when she states

that she believes the weather of the time was God’s punishment. Many people agreed

with her line of thinking. As a testament to this, quite a few churches were built in 1816

throughout New England.

There are many other accounts found in the newspapers of the time. One such

paper was the Virginia Argus, which, in their 22 June edition, included multiple

accounts of the weather conditions of the time. One such article, originally from the

“Bangor Register,” states that 5 June was warm and rainy, then continues to state that

around 2 in the afternoon on the 6th, snow started to fall and lasted an hour and a half.

Another article states that a letter arrived on 7 June from Chester, Vermont, saying that,

“There has been a remarkable change in the weather the three days past. The 5th was

at this place excessive warm. And the 6th was so cold that it was uncomfortable…

wearing loose garments- and this morning (the 7th) there was ice to the thickness of

half a dollar on bodies of standing water.”

The weather’s drastic mood swings continued to occur over the course of the

summer in an article entitled “Eighteen-hundred-and-frozen-to-death: 1816, The Year

Without a Summer,” the author Shirly T Wajda sites the diary of Reverend Thomas

Robbins when she states “On 22 August Robbins arose to frost on the ground. The

next day he observed that “the ground gets no relief from its drought." Robbins

continues stating that the 24th was "warm but things grow very little." This

unpredictable weather pattern would continue, with days swinging from rain to frost a

few days later. The newspapers for the month of August speak of severe hail storms

and fears of famine were seen in Connecticut. Giving fuel to these fears were reports of

rising milk prices due to crop failures.

September was not spared. In his diary, Robbins, in the entry for the 5th,

wonders if there has ever been a worse corn crop in their lifetime. What was left of this

crop would be finished by a deadly frost by the end of the month. The failure of this

and many other harvests kept food and fodder prices high.

The crops of the field failed, resulting in a large quantity of livestock perishing

over the course of the year. When the land was unable to provide alternative sources of

protein, it was made available from the sea. The fish spawning runs are the center of

the fisheries of New England and many other places around the world. The

temperature of the water induces spawning. Changing weather patterns meant that the

arrival of certain species of fish was irregular. Under an average pre-1816 year, the

Alewife would arrive first, followed by Mackerel. In 1816, the Mackerel arrived first.

These fish would be used, in part, in the barter economy. Proof of barter transactions

could be seen in newspapers of the day. For instance, Vermont maple syrup was

traded for Mackerel. For those that did not freeze to death, the ability to secure

Mackerel staved off the dark shadow of starvation that was taking so many and slowed

the effects of the malnutrition that would be felt for many years, especially by those

who were children during this period in time. An even more lasting impact of the "Year

of the Mackerel" is still with us today. Before 1816, the fish of choice was the Alewife

mentioned before. After this year, Mackerel was king.

Effects After 1816

These conditions continued for months. The climate would only start to turn and

stabilize to normal weather patterns in 1817. For many in New England, the choice was

to leave. Vermont alone saw a loss of 15,000 residents, or 10 percent of the population,

leaving many settling in northern New York while others headed to the Midwest. These

migrations arguably aided the push for westward expansion.

1816 provides humanity with a lesson we should heed. The effects of Mount

Tambora’s eruption show us how fragile our relationship with the environment and our

ability to survive as a species. While this monograph has focused on America, it is also

important to point out that effects were felt worldwide with widespread and deadly

consequences across most of Asia, especially China, Japan, and India. Flooding and

the continuing bouts of cold temperatures produced a famine in China that affected

Yunnan province until 1818. The failure of many other cash crops would see Yunnan

province emerge as a large-scale grower of opium poppies.

Opium was not the only deadly scourge that was brought forth as a consequence of the climate. Another would be a mutation of cholera. The new strain was unlike the strain that was endemic to the region around the Bay of Bengal. In contrast to the native strain, the population had no resistance. From Bengal, the new highly transmissible strain would spread around the world. Death would end up carrying off tens of millions of people across the globe in a pandemic that stretched until 1823.

The shadow of death also cast its veil over Europe as well. Europe was in the early stages of attempting to recover from the Napoleonic wars. The war’s cost was high, with 215,000 - 375,000 civilian casualties and at least 2 million casualties on the Allied side alone. Ireland endured eight weeks of nonstop rain, causing crops to rot. A famine-induced typhus epidemic ravaged the island till 1819, killing 40,000-100,000 people; for those that were left, the food shortages caused food riots across the British Isles.

The eruption of Mount Tambora combined with an extended period of lower-

than-average temperatures and the weather that comes with these conditions. The

combination that occurred in 1816 shows us parallels in our own time. The climate shift

shows us how delicate the climate is and our relationship with it. More importantly, for

reasons of self-preservation, 1816 shows our own human fragility. With temperatures

rising, what would happen if an eruption like Mount Tambora happened today? Would

our society be robust enough to weather the storms to come? Hopefully, we may learn

a lesson from our predecessor’s death and suffering. One wonders if we will.

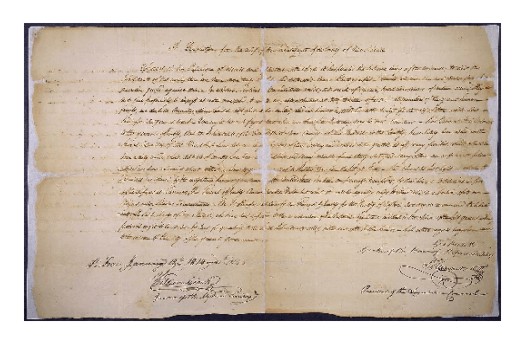

Image above: (Left) Painting entitled, "Crossing the Brook" that was inspired by the Year Without a Summer, also shown in other works by the author, 1815, J.M.W. Turner. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons. (right) Mount Tambora Caldera, 2009, NASA. Courtesy NASA and Wikipedia Commons. Image below: Drawing entitled, "Admit one person to the dinner at Guildhall, on Saturday Novr. 9th 1816," seemingly notes the Napoleanic War during the Year Without a Summer, 1816, Unknown. Courtesy Library of Congress. Source Info: Klingaman, William K. “Tambora Erupts in 1815 and Changes World History [Excerpt],” Scientific American, Mar. 2013; “Founders Online: Thomas Jefferson to Albert Gallatin, 8 September 1816.” Archives.gov, 2024; Huntington, Ray, and David Whitchurch. “Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death”: Mount Tambora, New England Weather, and the Joseph Smith Family in 1816. Albert; “Tambora: Making History.” VolcanoCafe, 19 Sept. 2023; DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE. “This Day in History: Mount Tambora Explosively Erupts in 1815.” NESDIS, 10 Apr. 2020; Volcano Hazards Program. “Pyroclastic Flows Move Fast and Destroy Everything in Their Path | U.S. Geological Survey.” Www.usgs.gov; “Mount Tambora Unveiled: 20 Facts That Will Leave You Awestruck.” Discover Walks Blog, 19 Jan. 2024; Landrigan, Leslie. “Six Ways the Little Ice Age Made History.” New England Historical Society, 15 Nov. 2017; Rafferty, John P. “Little Ice Age.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019; “New Worlds of Climate Change: The Little Ice Age and the Colonization of North

America.” HISTORICALCLIMATOLOGY.COM; Volcano Hazards Program. “Volcanoes Can Affect Climate | U.S. Geological Survey.” Www.usgs.gov, 2015; “1816 - the Year without Summer (U.S. National Park Service).” Www.nps.gov, 4

Apr. 2023; Landrigan, Leslie. “1816: The Year without a Summer.” New England Historical Society, 6 June 2014; Library of Congress; McLeod, Jaime. “1816: The Year without a Summer.” Farmers’ Almanac - Plan Your Day. Grow

Your Life., 22 Mar. 2010; “Eighteen-Hundred-And-Froze-To-Death: 1816, the Year without a Summer - Connecticut History | a CT Humanities Project.” Connecticut History, 17 Aug. 2020; “Lessons Learned from the “Year without a Summer:” a Call for Studying Climate Persistence.” The Panorama, 28 July 2023; “The Mackerel Year: Tambora Changed How New England Fished.” Earthmagazine.org, 2017; “Image 2 of the Rhode-Island Republican (Newport, R.I.), December 11, 1816.” Library of Congress; “The Year with No Summer Was a Brutal Shock for Half the World in 1816.” History Collection, 26 Aug. 2019; “The Eruption of Mount Tambora (1815-1818).” Climate in Arts and History;

“Napoleon, the Dark Side > the Human Cost of the Napoleonic Wars,” Napoleon.org; Maye, Brian. “A Volcanic Eruption with Global Repercussions – an Irishman’s Diary on 1816, the Year without a Summer.” The Irish Times, 19 Aug. 2016; Library of Congress - Newspapers.

History Photo Bomb

Effects After 1816

These conditions continued for months. The climate would only start to turn and

stabilize to normal weather patterns in 1817. For many in New England, the choice was

to leave. Vermont alone saw a loss of 15,000 residents, or 10 percent of the population,

leaving many settling in northern New York while others headed to the Midwest. These

migrations arguably aided the push for westward expansion.

1816 provides humanity with a lesson we should heed. The effects of Mount

Tambora’s eruption show us how fragile our relationship with the environment and our

ability to survive as a species. While this monograph has focused on America, it is also

important to point out that effects were felt worldwide with widespread and deadly

consequences across most of Asia, especially China, Japan, and India. Flooding and

the continuing bouts of cold temperatures produced a famine in China that affected

Yunnan province until 1818. The failure of many other cash crops would see Yunnan

province emerge as a large-scale grower of opium poppies.

Opium was not the only deadly scourge that was brought forth as a consequence of the climate. Another would be a mutation of cholera. The new strain was unlike the strain that was endemic to the region around the Bay of Bengal. In contrast to the native strain, the population had no resistance. From Bengal, the new highly transmissible strain would spread around the world. Death would end up carrying off tens of millions of people across the globe in a pandemic that stretched until 1823.

The shadow of death also cast its veil over Europe as well. Europe was in the early stages of attempting to recover from the Napoleonic wars. The war’s cost was high, with 215,000 - 375,000 civilian casualties and at least 2 million casualties on the Allied side alone. Ireland endured eight weeks of nonstop rain, causing crops to rot. A famine-induced typhus epidemic ravaged the island till 1819, killing 40,000-100,000 people; for those that were left, the food shortages caused food riots across the British Isles.

The eruption of Mount Tambora combined with an extended period of lower-

than-average temperatures and the weather that comes with these conditions. The

combination that occurred in 1816 shows us parallels in our own time. The climate shift

shows us how delicate the climate is and our relationship with it. More importantly, for

reasons of self-preservation, 1816 shows our own human fragility. With temperatures

rising, what would happen if an eruption like Mount Tambora happened today? Would

our society be robust enough to weather the storms to come? Hopefully, we may learn

a lesson from our predecessor’s death and suffering. One wonders if we will.

Image above: (Left) Painting entitled, "Crossing the Brook" that was inspired by the Year Without a Summer, also shown in other works by the author, 1815, J.M.W. Turner. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons. (right) Mount Tambora Caldera, 2009, NASA. Courtesy NASA and Wikipedia Commons. Image below: Drawing entitled, "Admit one person to the dinner at Guildhall, on Saturday Novr. 9th 1816," seemingly notes the Napoleanic War during the Year Without a Summer, 1816, Unknown. Courtesy Library of Congress. Source Info: Klingaman, William K. “Tambora Erupts in 1815 and Changes World History [Excerpt],” Scientific American, Mar. 2013; “Founders Online: Thomas Jefferson to Albert Gallatin, 8 September 1816.” Archives.gov, 2024; Huntington, Ray, and David Whitchurch. “Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death”: Mount Tambora, New England Weather, and the Joseph Smith Family in 1816. Albert; “Tambora: Making History.” VolcanoCafe, 19 Sept. 2023; DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE. “This Day in History: Mount Tambora Explosively Erupts in 1815.” NESDIS, 10 Apr. 2020; Volcano Hazards Program. “Pyroclastic Flows Move Fast and Destroy Everything in Their Path | U.S. Geological Survey.” Www.usgs.gov; “Mount Tambora Unveiled: 20 Facts That Will Leave You Awestruck.” Discover Walks Blog, 19 Jan. 2024; Landrigan, Leslie. “Six Ways the Little Ice Age Made History.” New England Historical Society, 15 Nov. 2017; Rafferty, John P. “Little Ice Age.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019; “New Worlds of Climate Change: The Little Ice Age and the Colonization of North

America.” HISTORICALCLIMATOLOGY.COM; Volcano Hazards Program. “Volcanoes Can Affect Climate | U.S. Geological Survey.” Www.usgs.gov, 2015; “1816 - the Year without Summer (U.S. National Park Service).” Www.nps.gov, 4

Apr. 2023; Landrigan, Leslie. “1816: The Year without a Summer.” New England Historical Society, 6 June 2014; Library of Congress; McLeod, Jaime. “1816: The Year without a Summer.” Farmers’ Almanac - Plan Your Day. Grow

Your Life., 22 Mar. 2010; “Eighteen-Hundred-And-Froze-To-Death: 1816, the Year without a Summer - Connecticut History | a CT Humanities Project.” Connecticut History, 17 Aug. 2020; “Lessons Learned from the “Year without a Summer:” a Call for Studying Climate Persistence.” The Panorama, 28 July 2023; “The Mackerel Year: Tambora Changed How New England Fished.” Earthmagazine.org, 2017; “Image 2 of the Rhode-Island Republican (Newport, R.I.), December 11, 1816.” Library of Congress; “The Year with No Summer Was a Brutal Shock for Half the World in 1816.” History Collection, 26 Aug. 2019; “The Eruption of Mount Tambora (1815-1818).” Climate in Arts and History;

“Napoleon, the Dark Side > the Human Cost of the Napoleonic Wars,” Napoleon.org; Maye, Brian. “A Volcanic Eruption with Global Repercussions – an Irishman’s Diary on 1816, the Year without a Summer.” The Irish Times, 19 Aug. 2016; Library of Congress - Newspapers.