Sponsor this page. Your banner or text ad can fill the space above.

Click here to Sponsor the page and how to reserve your ad.

- Timeline

1832 - Detail

April 8, 1832 - The Black Hawk War begins and would rage from Illinois to Wisconsin through September. It would consequently lead to the removal of Sauk and Fox Indians west, across the Mississippi River.

While the southeast was handling its native problem by Treaties, often unfair, that would lead to the Trail of Tears beginning later in the year, the midwest, from Illinois north was engaged in conflict. There was no secret that President Andrew Jackson was committed to pushing the remaining Indian tribes east of the Mississippi to the west of the Mississippi. The Treaty of 1804 had already established an Iowa Indian Territory, but members of the tribes there were not happy with its terms. They intended to reclaim some of the land ceded in that treaty, over fifty million acres for $2,234 and $1,000 per year. That land spanned an area on the east side of the Mississippi River from the Wisconsin River to the Missouri, and from the Illinois to the Fox Rivers.

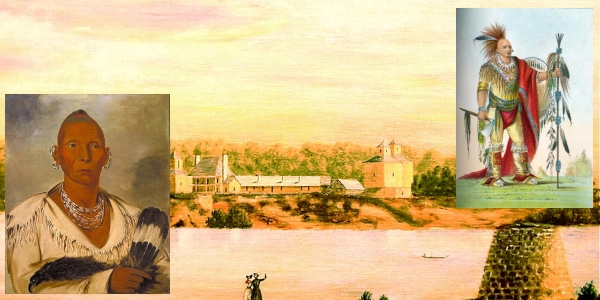

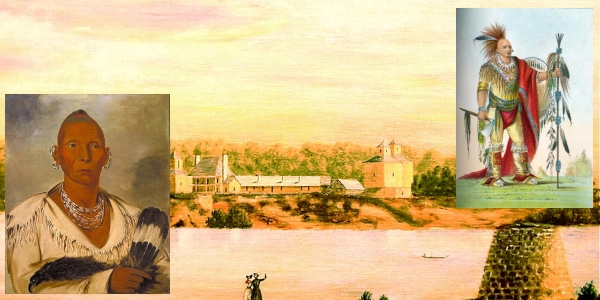

In April 1832, Black Hawk, leader of the Sauk (Sac), plus members of the Meskwakis (Fox) and Kickapoos left Iowa Indian Territory and crossed the Mississippi River into Illinois. A frontier militia called this group the British Band, and attacked them on May 14, 1832, sparking a series of battles that would last through September, now known as the Black Hawk War.

Black Hawk responded, attacking the militia at Stillman's Run the same day, causing a panicked retreat under Major Isiah Stillman. The British Band then moved north, into today's southern Wisconsin, under pursuit by the militia now headed by General Henry Atkinson. Other tribes began to take sides; the Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi supporting Black Hawk while the Menominee and Dakota chose to side with the United States.

U.S. forces under Colonel Henry Dodge caught up with Black Hawk on July 21, 1832, and defeated them at the Battle of Wisconsin Heights, near today's Sauk City. Dodge had between 600-750 men in his force; the British Band only 50-80, plus civilians. Although outnumbered, the tribes managed to delay the militia long enough to let the civilians escape. That escape was short-lived, as the militia caught up with the fleeing men, women, and children and massacred them at the Battle of Bad Axe on August 1, 1832.

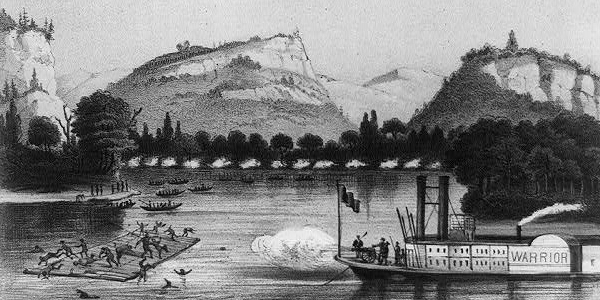

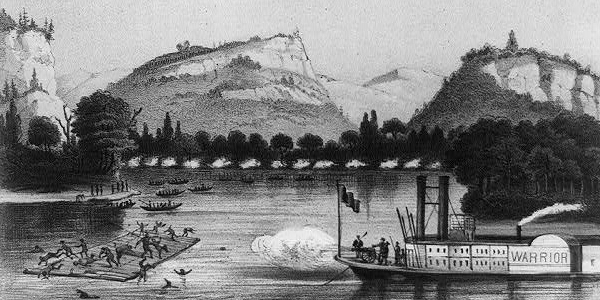

The battle along the Mississippi River a few miles south of the mouth of the Bad Axe River took place over two days. It would be the last battle of the war. U.S. forces, including Regular Army and Militia now numbered one thousand three hundred men; the entire British Band, including women and children, added to only five hundred. With the steamboat Warrior sailing along the water, the rafts of the Indians were under constant fire. Black Hawk attempted to surrender on the first day, but the militia did not understand his words.

On the second day, the remaining men of the British Band attempted to escape, but were pushed again toward the river. When the steamship Warrior returned, refueled, it sparked an eight hour battle that saw the militia kill one hundred and fifty warriors, plus women and children. They captured seventy-five more. Other escapees were later captured by Sioux allies of the U.S. Black Hawk himself escaped after the first day and was not present on the second.

Excerpt About the Battle

"During the engagement we killed some of the squaws through mistake. It was a great misfortune to those miserable squaws and children, that they did not carry into execution [the plan] they had formed on the morning of the battle -- that was, to come and meet us, and surrender themselves prisoners of war. It was a horrid sight to witness little children, wounded and suffering the most excruciating pain, although they were of the savage enemy, and the common enemy of the country," Major John Allen Wakefield, 1834.

Aftermath of the Black Hawk War

The casualties to the tribes at war greatly outnumbered that of the settlers and soldiers; four hundred and fifty to six hundred of the Sauk, Fox, and the other tribe warriors, women, and chidren to seventy-seven for U.S. forces. The casualty rate for the tribes represented about half of the number who had crossed the Mississippi River in April with Black Hawk. The captured, numbering about one hundred and twenty, were taken to Fort Amstrong; they were not released until General Winfield Scott, who arrived with a relief force, agreed. For most purposes, these Black Hawk War battles ended the Native American attacks in these areas and opened up Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin for greater settlement.

On August 20, 1832, Keokuk, a Sauk leader with friendlier relations with the U.S. Government, turned over Sauk and Fox chiefs who had been involved in the raids of the war. Keokuk also thought the Treaty of 1804 was a fraud, but considered, after sighting the size of eastern American cities, that a fight against it would be useless. It took until August 27, 1832, for Black Hawk, White Cloud, and the remaining warriors of the British Band to surrender.

A Parade of Indians

After Black Hawk's capture, Colonel Zachary Taylor sent the prisoners, twenty in number, to Jefferson Barracks, escorted by Lt. Jefferson Davis, future President of the Confederacy, and Robert Anderson. Most were released within several months. However, six, including Black Hawk, Wabokieshiek, and Neapope were transferred to Fort Monroe in Virginia in April 1833. The trip east became a trip of celebrity and humiliation, as crowds would gather at each stop to see the captives. At Louisville and Cincinnati, large crowds gathered. They met President Jackson at Washington, and were transported for incarceration at Fort Monroe that lasted only a few weeks.

The U.S. Government thought that touring the captured chiefs would discourage others from attacking, and encourage them to make treaties and head to the reservation. From June 1833, they toured Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City. They were treated well, but as a spectacleat the same time. Period cartoons would depict Black Hawk in some as more hero that that of President Jackson, whose resettlement policies were not universally popular. However, in the end, Black Hawk would live out his life in Iowa, and even attempted a reconciliation with Keokuk.

Note: the date of when Black Hawk crossed the Mississippi River with the British Band has varying dates according to many sources; most range from August 5, 1832 to August 8, 1832.

Image above: Montage (background) Fort Amstrong, 1839, Octave Blair; (left inset) Chief Black Hawk, leader of the Sauk (Sak), 1832, George Catlin, Smithsonian; (inset right) Keokuk (Running Fox), 1832/1839, George Catlin. All courtesy Wikipedia Commons. Below: Illustration of the Battle of Bad Axe (American steamship, the Warrior, firing at Indians on a raft), 1857, Henry Lewis Engraver. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info Source: "The Black Hawk War Introduction," James E. Lewis, Kalamazoo College; Wikipedia Commons; Library of Congress.

History Photo Bomb