Indian petroglyphs mentioned in the journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Nemaha River, Troy, Kansas. Courtesy National Archives. Right: Historic New Orleans wharf scene along the Mississippi River. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Sponsor this page for $125 per year. Your banner or text

ad can fill the space above.

Click here to Sponsor the page and how to reserve your ad.

-

Timeline

1801 Detail

January 20, 1801 - John Marshall is appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

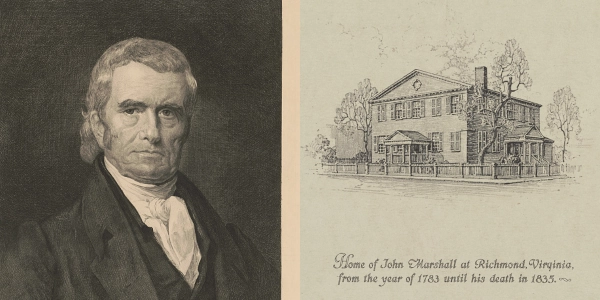

John Marshall would become the longest tenured Supreme Court Chief Justice in history, serving for thirty-four years. His nomination on January 20, 1801 came through President John Adams where he had been serving as Secretary of State. Adams was not the only one impressed with his qualifications for both jobs. Marshall maintained the job of Secretary of State and Chief Justice, the fourth in our nation's young history, through the end of Adams' term, as well as the beginning of the first term of President Thomas Jefferson. You ask, how long did it take for the Senate to confirm him? John Marshall was confirmed on January 27, 1801, seven days after his appointment. Apparently, in an age without computers and a team of investigators to comb through his past writings or problems, the Senators of the day could make up their own minds.

How Did Marshall Rise to the Position

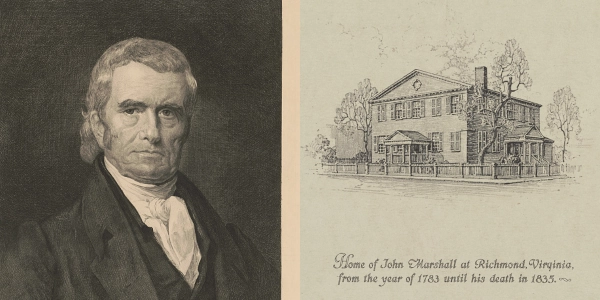

Marshall was born in 1755 in Germantown, Virginia, at the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. the oldest of fifteen children to Thomas Marshall and Mary Randolph Keith. He lived in the state the majority of his life. His later home, in Richmond, was the justice's resident from 1783 to 1835.

His goal before the American Revolution began was to be a lawyer, which he put on hold to serve in the Revolutionary War from 1775 to 1780 as an officer in the Continental Army. Marshall particpated in the Battle of Brandywine, the largest battle of the war, Germantown, and Monmouth, serving alongside General George Washington. He weathered the winter at Valley Forge. One of his first flirts with law came at the encampment, when, on February 5, 1778, John Marshall assisted the Judge Advocate General as his deputy in proceedings of court martials and other punishments.

His goal after service was again to become a lawyer, which he did through law lectures under the first law professor in the United States, George Wythe, at William and Mary College, as well as private study. He was admitted into practice in 1780. He was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates three times, then in 1797, he accepted the position as one of three envoys on a diplomatic mission to France during the XYZ Affair. Although it is hard to imagine turning down a position on the highest court of the land, at the end of the 18th Century and beginning of the 19th Century, the position did not have the allure of a Representative, Senator, or Governor. Marshall turned down a postion as associate justice in 1798, choosing private practice and a run (selection as) for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1799 and believed in Federalist values. His appointment as Secretary of State came only one year later.

The Marshall Court

By the end of the Marshall Court in 1835, the prestige of the institution had grown. It would no longer be the little brother of the other two branches and would be a desired office to be appointed to. Most scholars think that the rise of prestige and bringing equality to the judiciary on par with the executive and legislative branches can be directly attributed to how John Marshall ran the court. It was his assertion that the Constitution reigned as paramount, and that the decisions of the other branches must adhere to it. An early test of that philosophy came in the 1803 case of Marbury versus Madison.

Chief Justice Marshall also exerted, through his reading of the Constitution, that the powers of the Federal government, if conflicting with a state government, superceded that of the state. He was known for great intellect and the ability to build consensus around an opinion. Many opinions in the Marshall Court were unanimous. Despite reaching that consensus in his day, Marshall was concerned whether the court and the Constitution would ultimately fail due to the question of states right.

Today, you can visit a statue of the Chief Justice by William Wetmore Story in Marshall Memorial Park, which is located between the Canadian Embassy and the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. Another statue, titled The Chess Players by Lloyd Lillie, is located on the east side of the park, reflecting one of his favorite pastimes.

Photo above: Montage (left) Etching of Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, 1895, James Fagan; (right) Etching of the home of John Marshall in Richmond, Va., 1820/1835, unknown author. Both courtesy of the Library of Congress. Below: Ceiling mural in U.S. Capitol of Chief Justice giving Oath of Office to President Andrew Jackson in 1829, 1973/4, Allyn Cox. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info source: Library of Congress; supremecourthistory.com; "John Marshall, the Great Chief Justice," William and Mary Law School; Wikipedia Commons.