Sponsor this page for $150 per year. Your banner or text ad can fill the space above.

Click here to Sponsor the page and how to reserve your ad.

-

Timeline

1755 Detail

July 25, 1755 - Decision to relocate Acadian French from Nova Scotia is made. British relocate 11,500 Acadian French to other British colonies and France over the next eight years; some later settle in Louisiana.

It was amidst the last of the four French and Indian Wars, the one we refer to as the only French and Indian War too many times, and the British were tiring of any French citizens anywhere near their occupied territory. For Acadia, this meant Nova Scotia, battled over many times, with the French nearby on Cape Breton. After all, the Treaty of Ultrecht that had ended another of those four wars, Queen Anne's War, had awarded Nova Scotia to the English.

Of course, the French had been contending that Nova Scotia was their territory to colonize for nearly two hundred years prior to that Treaty of Ultrecht, basically ever since Giovanni da Verrazzano, working for the French, had explored the area in 1524 with settlement of the region at the start of the 17th century at Port Royal in 1604-5. The Acadians were always independent minded and not purely loyal to the French. They became friends with the Mi'kmaq tribe and attempted to accept the change to British rule.

Although life for the Acadian French did not change much directly after the British took control, they were never trusted. In 1730, they took a neutrality oath, swearing that if war ever started again, they would not take sides for either the British or French. This lasted for nearly twenty years until the Seven Years War, the north American section known as the final French and Indian War we know most about, began and the French now had built a large naval fortress on Cape Breton at Louisbourg. The British countered by building a naval base at Halifax. That was followed, in 1751, by the French building another fort, Fort Beauséjour with the English countering again, Fort Lawrence, not far from the French fort.

However, the British Lt. Governor of Nova Scotia, Charles Lawrence, was not pleased, and did not trust the neutrality of the Acadian French. When the British defeated the French at Fort Beauséjour in June 1755, there were two hundred and seventy Acadian fighting for the French. So he ordered the remainder to take a pledge of allegiance to Britain. They refused, some due to the treatment by the British, others because of religious views that denied their Catholic faith with the King of England they would be pledging to, also the Head of the Church of England, which was Protestant. So Lawrence had them put in prison, and soon after, July 25 (28), 1755, the town council voted to expell the Acadian French from Nova Scotia.

Deportation orders first circulated on August 11, 1755. Then on September 5, 1755, a decree was read to all Acadian males ten years old and up, who were rounded up by Colonel John Winslow in the town church.

"That you Land & Tennements, Cattle of all Kinds and Livestocks of all Sorts are forfeited to the Crown with all other your effects Savings your money and Household Goods, and you yourselves to be removed from this Province," Gov. Charles Lawrence, read by Colonel John Winslow.

The Great Upheaval

Upon making the decision to expel them, the British rounded up the Acadian French, burning some of their homes and crops, then placed them on ships bound for and spread about the thirteen colonies. Some fought back, but were easily defeated. Others fled, either to the forests or territories of New France. It is estimated that fifteen hundred made it to settlements of New France. However, by fall of 1755, one thousand and one hundred were transported away from Nova Scotia to the colonies of South Carolina, Georgia, and Pennsylvania. The remainder, totaling nearly ten thousand (some reports note up to eighteen thousand), over the next eight years, were transported to the other colonies, some back to France, and others began to gather in Louisiana, becoming today known as Cajuns. It is untrue that the British transported them there, but that they were attracted by the culture there when their brethren began to gather in Louisiana, transported there from France on five Spanish ships after their deportation back to France by the British.

The outcome for many of the Acadian French was not as fortunate as those that made it to Louisiana. Many starved or succumbed to disease along all of the transports; other were forced into labor servitude in other British colonies.

Some were allowed to return to Nova Scotia in 1764 in small groups, but they came back to farms that had been given to English families, something the British had wanted for forty years.

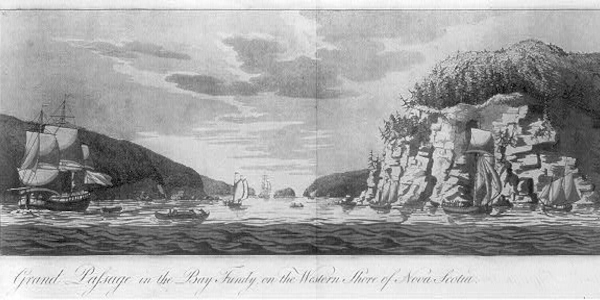

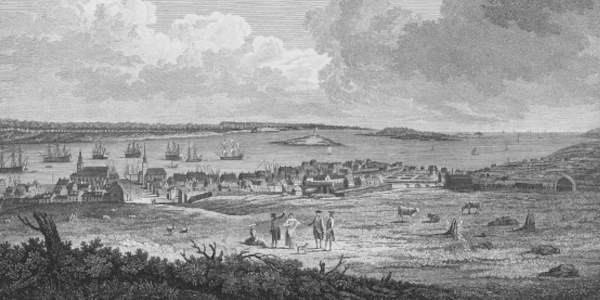

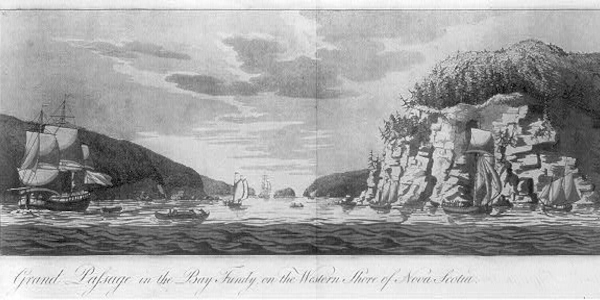

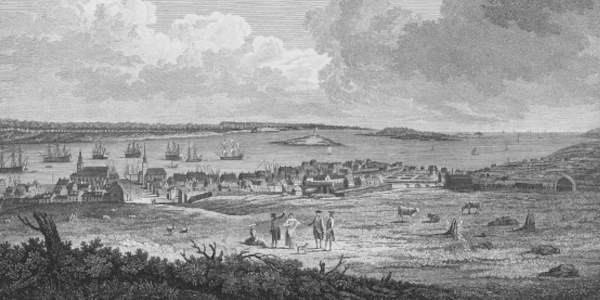

Image above: Illustration of the town of Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1764, Engraver James Mason, Artist Dominique Serres. Courtesy Library of Congress. Image Below: Drawing of the Grand Passage from the Bay of Fundy, west side of Nova Scotia, 1780, Joseph F.W. Des Barres, the Atlantic Neptune, published for British Royal Navy. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info Source: "Acadian Expulsion," 2021, thecanadianencyclopedia.ca; "Acadian Affairs and Francophonie," novascotia.ca; Wikipedia Commons.

History Photo Bomb

It was amidst the last of the four French and Indian Wars, the one we refer to as the only French and Indian War too many times, and the British were tiring of any French citizens anywhere near their occupied territory. For Acadia, this meant Nova Scotia, battled over many times, with the French nearby on Cape Breton. After all, the Treaty of Ultrecht that had ended another of those four wars, Queen Anne's War, had awarded Nova Scotia to the English.

Of course, the French had been contending that Nova Scotia was their territory to colonize for nearly two hundred years prior to that Treaty of Ultrecht, basically ever since Giovanni da Verrazzano, working for the French, had explored the area in 1524 with settlement of the region at the start of the 17th century at Port Royal in 1604-5. The Acadians were always independent minded and not purely loyal to the French. They became friends with the Mi'kmaq tribe and attempted to accept the change to British rule.

Although life for the Acadian French did not change much directly after the British took control, they were never trusted. In 1730, they took a neutrality oath, swearing that if war ever started again, they would not take sides for either the British or French. This lasted for nearly twenty years until the Seven Years War, the north American section known as the final French and Indian War we know most about, began and the French now had built a large naval fortress on Cape Breton at Louisbourg. The British countered by building a naval base at Halifax. That was followed, in 1751, by the French building another fort, Fort Beauséjour with the English countering again, Fort Lawrence, not far from the French fort.

However, the British Lt. Governor of Nova Scotia, Charles Lawrence, was not pleased, and did not trust the neutrality of the Acadian French. When the British defeated the French at Fort Beauséjour in June 1755, there were two hundred and seventy Acadian fighting for the French. So he ordered the remainder to take a pledge of allegiance to Britain. They refused, some due to the treatment by the British, others because of religious views that denied their Catholic faith with the King of England they would be pledging to, also the Head of the Church of England, which was Protestant. So Lawrence had them put in prison, and soon after, July 25 (28), 1755, the town council voted to expell the Acadian French from Nova Scotia.

Deportation orders first circulated on August 11, 1755. Then on September 5, 1755, a decree was read to all Acadian males ten years old and up, who were rounded up by Colonel John Winslow in the town church.

"That you Land & Tennements, Cattle of all Kinds and Livestocks of all Sorts are forfeited to the Crown with all other your effects Savings your money and Household Goods, and you yourselves to be removed from this Province," Gov. Charles Lawrence, read by Colonel John Winslow.

The Great Upheaval

Upon making the decision to expel them, the British rounded up the Acadian French, burning some of their homes and crops, then placed them on ships bound for and spread about the thirteen colonies. Some fought back, but were easily defeated. Others fled, either to the forests or territories of New France. It is estimated that fifteen hundred made it to settlements of New France. However, by fall of 1755, one thousand and one hundred were transported away from Nova Scotia to the colonies of South Carolina, Georgia, and Pennsylvania. The remainder, totaling nearly ten thousand (some reports note up to eighteen thousand), over the next eight years, were transported to the other colonies, some back to France, and others began to gather in Louisiana, becoming today known as Cajuns. It is untrue that the British transported them there, but that they were attracted by the culture there when their brethren began to gather in Louisiana, transported there from France on five Spanish ships after their deportation back to France by the British.

The outcome for many of the Acadian French was not as fortunate as those that made it to Louisiana. Many starved or succumbed to disease along all of the transports; other were forced into labor servitude in other British colonies.

Some were allowed to return to Nova Scotia in 1764 in small groups, but they came back to farms that had been given to English families, something the British had wanted for forty years.

Image above: Illustration of the town of Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1764, Engraver James Mason, Artist Dominique Serres. Courtesy Library of Congress. Image Below: Drawing of the Grand Passage from the Bay of Fundy, west side of Nova Scotia, 1780, Joseph F.W. Des Barres, the Atlantic Neptune, published for British Royal Navy. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info Source: "Acadian Expulsion," 2021, thecanadianencyclopedia.ca; "Acadian Affairs and Francophonie," novascotia.ca; Wikipedia Commons.