Sponsor this page. Your banner or text ad can fill the space above.

Click here to Sponsor the page and how to reserve your ad.

-

Timeline

1780 Detail

May 12, 1780 - Charleston, South Carolina falls to the British after an effective siege.

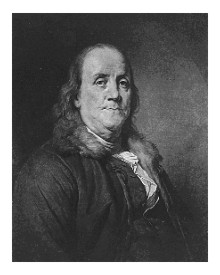

The British understood that the forces guarding Charleston were insufficient to battles such a significant armada. The Americans defending the city under General Benjamin Lincoln, who had been appointed U.S. Commander of the South on January 2, 1779, counted only six thousand five hundred and seventy-seven men at his disposal, and despite a small victory in February in the Battle of Beaufort by General Moultrie, and more actions in the 1779 campaign, the American forces were still more green than their counterparts. Washington was aware that the British would likely attack soon, but could not give Lincoln additional men due to his bogged down position outside British controlled New York. General Clinton's initial plan included bypassing Charleston and meeting up with the ground forces of Lt. Colonel Mark Prevost in Savannah. The sail south through the harsh winter cost Clinton ships, time, and men. A normal voyage of ten days extended to five weeks.

They finally arrived on February 11, 1780, on today's Seabrook Island, far enough from Charleston to stay quiet to their enemy. The terrain to cross was difficult, but they crossed the Stono River and controlled James Island by March 1, 1780. By March 29, they had navigated the Ashley River. On April 1, 1780, the British started their first siege parallel. The American defense was fortifications along the Charleston Neck between the rivers. Unfortunately, on the same day, April 8, that American reinforcements arrived, the British warships raced past Fort Moultrie and now controlled Charleston Harbor. The American navy under Commodore Abraham Whipple scuttled their ships in the harbor as obstacles. Now there was no way to escape or get supplies for the Continental forces or the Charleston citizens who remained.

"April 1780 ... Marched to Draytons.

Reconnoitred landing; chose the lower, over-persuaded by Robertson. Landed at upper without a shot, halted the night at Ashley Ferry.

Marched next day to Gibbs; Lord Caithness wounded CLOSE TO ME. Lord Corwallis UNSOLDIERLY BEHAVIOR, NEGLECTING TO GIVE ORDERS IN MY ABSENSE, WHICH IF Andre DID, HE OWNS MYSELF WAS WRONG. 'Tis certainly so, for when Andre applied to him he did not ORDER THE LIGHT INFANTRY NOR CANNON FOR some time. THE LIGHT INFANTRY WAS NOT 200 yards from the post attacked. I went to the left on the island, saw rising ground near the town which appeared not above 800 yards from it. I showed it to Moncreiff who agree. I desired Lord Cornwallis to view it.

Moncrieff proposed to throw up redoubts; three he intended, but having tools only for one redoubt, it was thought better to defer till next day. Moncrieff first intended a line to support them before he raised the redoubts, but afterwards thought better of it.

At night everything prepared for our move. At 8 o'clock we broke ground within 800 yards of the place, and in one night completed three redoubts and a communication without a single shot. I had given directions, in case of interruption, that they should be threatened from the other side. ....," General Henry Clinton.

Reconnoitred landing; chose the lower, over-persuaded by Robertson. Landed at upper without a shot, halted the night at Ashley Ferry.

Marched next day to Gibbs; Lord Caithness wounded CLOSE TO ME. Lord Corwallis UNSOLDIERLY BEHAVIOR, NEGLECTING TO GIVE ORDERS IN MY ABSENSE, WHICH IF Andre DID, HE OWNS MYSELF WAS WRONG. 'Tis certainly so, for when Andre applied to him he did not ORDER THE LIGHT INFANTRY NOR CANNON FOR some time. THE LIGHT INFANTRY WAS NOT 200 yards from the post attacked. I went to the left on the island, saw rising ground near the town which appeared not above 800 yards from it. I showed it to Moncreiff who agree. I desired Lord Cornwallis to view it.

Moncrieff proposed to throw up redoubts; three he intended, but having tools only for one redoubt, it was thought better to defer till next day. Moncrieff first intended a line to support them before he raised the redoubts, but afterwards thought better of it.

At night everything prepared for our move. At 8 o'clock we broke ground within 800 yards of the place, and in one night completed three redoubts and a communication without a single shot. I had given directions, in case of interruption, that they should be threatened from the other side. ....," General Henry Clinton.

The Siege Intensifies

On April 10, General Clinton sent word to General Benjamin Lincoln to surrender. Lincoln said he would defend the city. British bombardments began on April 13. A second parallel by the British brought their guns closer after its completion on April 17. Now Lincoln, after a council or war in which the military favored evacuation, but the civilians wanted to continue fighting, he sent word to Clinton on April 22 that he would surrender the city if his men, troops, were allowed to leave into the backcountry. The British said no, and continued their shelling of the city.

21 April. General Leslie reported that the first parallel is finished completely; ordered guns, etc. into it as Moncrieff desires. About 11, Gen Lincoln sent to propose a cessation and terms as sent to the Admiral. Gave them the six hours asked, but for Lord Cornwallis, who was clear of opinion we should give them the same terms offered at first and not plunder them. Admiral exactly the same. General Leslie would give no opinion. Some messages passed, but it ended in their sending terms proposed, which could not be listended to. An ultimatum was sent, exactly what we sent before, which they refused by a verbal message, for none other would they send, that General Lincoln could not accept the terms offered, and I might begin to fire against as soon as I would, which accordingly happened at half past ten, directing all the fire to the banks of the river to prevent their going off by water. The moment the Admiral arrived he told me "that if it had not been for those rascal's sending the message, his small vessels would go into Cooper River this night." MUM, of course. I told him finally that if he found that so practicable, he had better send them this night. He said he had or would order it, and he wrote his letter ordering them to proceed, and Capt Hudson, if he saw occasion, to obey further orders, which he insinuated was to attack Fort Sullivan with all the large ships. This was all proposed before he received the final answer. Moncrieff reported this," General Henry Clinton."

For fourteen days, the British troops moved closer and closer to the American lines; a third parallel having been completed. By May 8, the distance between the forces had been reduced to yards. General Henry Clinton asked for unconditional surrender. General Lincoln refused. After days of now bombarding Charleston with heated shot, causing the city to burn, the American finally surrendered. Five thousand soldiers of the Continental Army were immediately captured, almost the entire American force in the area. Two thousand five hundred were imprisoned; many of which did not survive. Three hundred cannon were captured, along with six thousand muskets.

End of the Siege and Its Aftermath

The siege would end on May 12, 1780. There had been only two hundred and fifty-eight British casualties; killed, wounded, and missing for the Americans, five thousand five hundred and six. For Great Britain, this great success led to a feeling that elevated Sir Henry Clinton to his highest point in the war. They thought they could capture the South easily. They would be wrong. First, General Clinton left the south, leaving General Cornwallis in command. And Cornwallis made a fatal mistake on June 1, 1780; he parolled and released many of the remaining prisoners as long as they stated loyalty to the King. There was no loyalty. So the American Revolution in the South was just beginning, now with renewed fervor; battles such as Camden, Waxhaws, Cowpens, King's Mountain, Guilford Courthouse, and Ninety-Six, would be won easily by the British, then lost hard.

And what happened to Major General Benjamin Lincoln? He became a prisoner after the siege, but was exchanged for British Major General William Phillips later that year. Once again, they should not have done this, because the General, once again part of General Washington's Continental Army, became a major contributor at the Battle of Yorktown when Washington's forces overcame General Cornwallis and won the American Revolution. General Lincoln participated in the surrender.

At 2:00 P.M. French and American troops began to move into British positions at the east end of the town. With American troops lined up on the right and French on the left, the British began their march through the lines, "their Drums in Front beating a slow March. Their Colours furl’d and Cased . . . General Lincoln with his Aids conducted them—Having passed thro' our whole Army they grounded their Arms & march’d back again thro' the Army a second Time into the Town - The sight was too pleasing to an American to admit of Description" (TUCKER, 392–93). French army officer baron von Closen noted that in passing through the lines the British showed "the greatest scorn for the Americans, who, to tell the truth, were eclipsed by our army in splendor of appearance and dress, for most of these unfortunate persons were clad in small jackets of white cloth, dirty and ragged, and a number of them were almost barefoot" (CLOSEN, 153). Cornwallis, claiming illness, did not accompany his troops, and the surrender was carried out by Brig. Gen. Charles O’Hara, who had accompanied Cornwallis through the Carolina campaign. The British officer's sword was accepted by Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln," General George Washington, October 19, 1781.

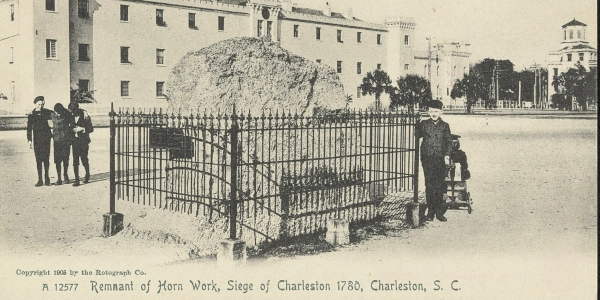

Photo above: Siege of Charleston 1780, Alonzo Chappel. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons, Brown University. Below: Postcard of the Remnant of Horn Work, Siege of Charleston 1780, 1905, Sol-Art Prints; The Rotograph Co. Courtesy Library of Congress. Sources: "Siege of Charleston 1780," Joseph C. Scott, U.S. Army, mountvernon.org; "Siege of Charleston 1780," National Park Service; Library of Congress; Wikipedia Commons; American Battlefield Trust;

Sir Henry Clinton's "Journal of the Siege of Charleston, 1780," Henry Clinton and William T. Bulger; "Washington's Diary Entry, October 19, 1781," George Washington, founders.archives.org.