Sponsor this page. Your banner or text ad can fill the space above.

Click here to Sponsor the page and how to reserve your ad.

-

Timeline

1912 - Detail

August 4, 1912 - The United States Marines are sent to action in Nicaragua due to its default on loans to the United States and its European allies and protect U.S. business interests.

The normal notion of debt collection is a somewhat shady character, or bank letter, sent to your house. The idea that debt collection, on a national scale between nations, means the U.S. Marines board ship and head to your harbor, is a bit odd in today's terms with international banking and ecommerce solutions. But that was not the way things worked in 1912.

One of President William Taft's policies toward Latin America was known as dollar diplomacy. He believed that investing in those countries would assist in applying the Monroe Doctrine without getting physically involved, as well as lessen European influence there. One of the first test of that policy came in Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. Mexican rebels would cross the U.S. border to trade for horses and weapons. Taft attempted to prop up the current dictator Porfirio Díaz by sending the Army to the border for maneuvers and meeting with the dictator twice. When Taft went for the second meeting, this time in Mexico, a plot to assassinate was thwarted, whether meant for one or both. None of this stopped the Mexican Revolution from happening after supporters of his opponent, Francisco Madero, was jailed, and a full scale revolution followed for ten years.

Dollar diplomacy was also occurring with Nicaragua, although the instability of the country, under various presidents, and after several coups, forced the United States into action. First, President Zeleya wanted to revoke concessions to American companies. His successor, Madíz, could not stop rebel forces, so the United States interfered. The U.S. was concerned that the alternate route for the Panama Canal, the preferred, to them, Nicaraguan Canal, should not fall into European or Japanese hands, so they backed the rebel forces under Juan Estrada, who took the capital in 1910. They recognized his government officially. With him in power, the United States forced Nicaragua to accept a loan, a new constitution, the end to monopolies, plus sending officials to ensure payment from their treasury. However, instability continued; another coup occurred in 1911.

Taft took action again. He made multiple attempts with his Dollar Diplomacy policy, allowing American banks to effectively control Nicaragua's finances. But these were fragile loans.

The Occupation

The deteriorating condition of Nicaragua's finances forced Estrada to resign, replacing him was his Vice President, a Conservative named Adolfo Díaz. However, the Secretary of War, Luis Mena, did not approve of his connection to the United States, and told Díaz that he would take over in 1913 when his term was done. This was backed by the Nicaraguan National Assembly. Many Nicaraguan citizens were concerned that a foreign nation was taking over their banking system, railroad, and political systems. In many ways, they were right.

Secretary of State Philander C. Knox convinced President Taft that this was not acceptable; U.S. citizens had already been killed and he had demanded that there be prosecution of their attackers. The control of the railroad from Corinto to Granada was impacting U.S. interests. Taft agreed to continue supporting Díaz. Mena and his forces revolted, capturing two ships that were owned by U.S. companies. The rebels attacked the capital with a four hour bombardment, putting U.S. officials in jeopardy. A cable was sent to Washington that troops were needed to safeguard U.S. citizens, officials, and interests.

In one of the conflicts known as the Banana Wars in Central America and South America, the President sent troops to Nicaragua to ensure payment and provide stability. The USS Annapolis was patrolling the Bluefields coastline with one hundred Marines onboard. Three hundred and fifty Marines returned from Panama to assist. Commanding all forces was Admiral William Henry Hudson Southerland. He was joined by Colonel Joseph Henry Pendleton and seven hundred and fifty Marines. With their arrival, Mena left the country.

The occupation of Nicaragua would begin in 1912 and not end until 1933 when President Herbert Hoover stopped the intervention.

There are a variety of dates associated with the arrival of U.S. Marines sent to quell the rebellion, occupy the country, and safeguard U.S. citizens and interests, including that railroad line and potential canal route. They range from August 4, 1912 to August 14, 1912. We have chosen August 4 as it is the earliest that has been noted of U.S. occupation within the 1912 intervention.

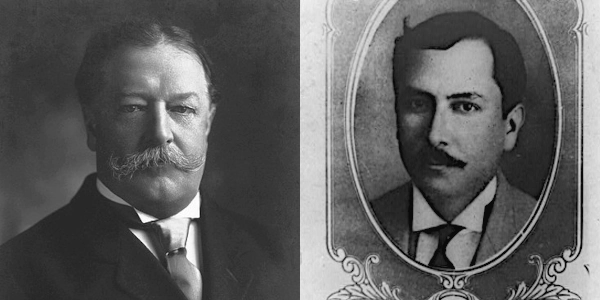

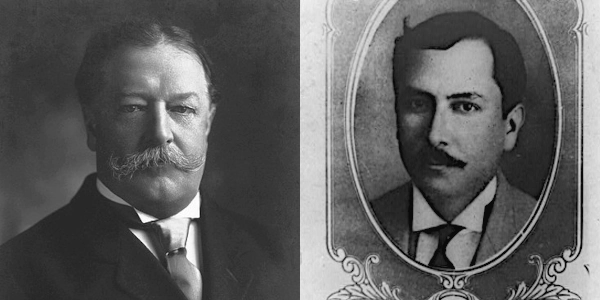

Photo above: Landing force of the USS Denver, 1912, U.S. Navy Photographer. Courtesy U.S. Navy via Wikipedia Commons. Photo below: Montage (left) President William H. Taft, date unknown, Harris and Ewing. Courtesy Library of Congress via Wikipedia Commons; (right) Don Adolpho Díaz, President of Nicaragua, Bain News Service. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info source: "U.S. Intervention in Nicaragua, 1911/1912," U.S. Department of State; "History: the Occupation of Nicaragua," nicaragua.com; Wikipedia Commons.

History

Photo Bomb