Sponsor this page. Your banner or text ad can fill the space above.

Click here to Sponsor the page and how to reserve your ad.

-

Timeline

1971 - Detail

January 2, 1971 - A ban on the television advertisement of cigarettes goes into affect in the United States.

Article by Jason Donovan

The twentieth century saw an explosion of ads for cigarettes throughout the media of the day.

The new medium of television was no exception. From the start of television advertising,

cigarette companies had a stranglehold on what was seen on all the networks. During the

1950s and 1960s, known as the "Golden Age of Television," cigarette advertisements saturated

almost all programs. At the same time, the medical research results were coming in, and the

results were not good for anyone. Cigarette ads on television were on borrowed time. That is,

until 2 January 1971, when a governmental ban on these advertisements on television took

effect.

The tobacco industry in the United States has, from the beginning of the country, been

a key industry, as tobacco has been a cash crop for many farmers across the nation. There

has always been some advertising associated with the industry, but then came the cigarette.

Advertising was, in the beginning of the twentieth century, confined to print media. As the

century progressed and technology advanced, radio and then television, the cigarette

companies moved their advertising to these platforms in turn.

Cigarette companies in the mid-twentieth century wielded their power over the

television networks. The company ordered the show, bought it, told the networks which time

slot to put it, and then included a large advertising segment in the middle of the show itself.

This absolute power allowed them to have complete control over the narrative about the

"benefits of cigarettes." The iron grip that the behemoth tobacco companies had on the

narrative started to slip in 1952.

The Reader's Digest for December 1952 had a bombshell article entitled "Cancer By

The Carton.. Cancer By The Carton lays out, by the numbers, the reality behind the pro-

cigarette narrative being pushed at the time. Contrary to what all the doctors, who were being

beamed continuously into American living rooms, were stating, there were no ill health effects

associated with smoking.

Medical Study

According to the article a study that appeared in the 27 May 1952 edition of "The

Journal of the American Medical Association," a well-known group led by a former president of

the American Cancer Society, and director of the famous Ochsner Clinic in New Orleans,

shows a massive rise in cancers. The article continues with the cold numbers stating, "1920 to

1948 deaths from bronchiogenic carcinoma in the United States increased more than ten times

from 1.1 to 11.3 per 100,000 of population." Although this may look like a stunning increase, it

is nothing compared to the period of 1938 to 1948. During that period of time, a conflagration

of cancer deaths occurred with a rise of 144 percent. In 1952, mouth and respiratory cancers

accounted for the deaths of 19,000 men and 5,000 women, and were on the verge of

becoming "more frequent than any other cancer of the body."

The article cites a study conducted by the Medical Research Council of England and

Wales that found "above the age of 45 the risk of developing the disease increases in simple

proportion with the amount smoked, and may be fifty times as great among those who smoked

twenty five or more cigarettes daily as among nonsmokers." A researcher in another study by

the name of Ernest L. Wynder with the Memorial Cancer Center in New York gives a blunt

assessment when he states, "The more a person smokes the greater the risk of developing cancer of the lung, whereas the

risk was small in a nonsmoker or a light smoker." With the research showing a connection

between adverse health effects and smoking started to pile up the federal government would

get involved.

Government Legislation

The first time the federal government intervened was in 1964. The ball got rolling when

the Surgeon General released a report on 11 January 1964. The report concluded that

"cigarette smoking was a health hazard warranting "appropriate remedial action." Then another

government body got involved when the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) said in June of 1964

that, as of 1 July 1965, warning labels stating the health effects of smoking would be required

on cigarette packaging. Big tobacco did not just lie down and accept this requirement. The

industry launched a two-pronged effort to derail the requirement. First, they plowed money into

a lobbying offensive on Congress. Secondly, they launched a charm offensive with the public, by, in part, reminding them of the industry's importance in the economic health of the country's economy.

Further government action came in the form of Senate bill S. 599. This legislation was

introduced by the head of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Washington's Senator Warren

G. Magnuson, on 15 January 1965. This bill set the required warning language as "Warning:

Continual Cigarette Smoking May be Hazardous to Your Health." The bill also proved that the

lobbying offensive was effective. The bill shut down the FTC by banning any further warnings

by federal, state, and local governments from being added to packaging. This language

effectively removed the FTC from issuing any further regulation on both labeling and

advertising of any kind. The House of Representatives action would follow soon after.

Legislation came in the form of H.R. 3014, which was introduced to the House by

Walter Rogers of Texas. This bill also included language regulating the FTC, but unlike the

three-year ban in the Senate bill, the House bill made the ban permanent. The bill moved to the

House Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee, and on 28 June, the committee advised

the House that the bill had passed the committee 23 to 8. A floor vote motion that Illinois

Representative Donald Rumsfeld introduced was defeated. In contrast, a voice vote passed the

bill on 22 July. Big Tobacco was not the only group that was squeezing Congress for

favorable action. Health advocates engaged in their lobbying offensive. These groups pushed

for providing the public with even more information on the health effects and the industry's

interests in curtailing the government providing such information. Pro information groups

included left-leaning groups such as Americans for Democratic Action, which deemed the bill

passed by the Senate as "at least tolerable," while advising President Johnson to veto any

legislation that includes a permanent ban on the FTC. Then the chairman of the FTC offered his

opinion on the situation.

The chairman, Paul Rand Dixion, wrote to Senator Magnuson in May of 1965. Dixion

continued to state the agency's position "that warnings in cigarette advertising, not just labels

on packages, would more fully inform the public of the hazards of cigarette smoking." He

continued by stating that the public needs to be better informed, and to achieve this, the

agency should not be limited in its efforts to regulate the industry. Dixon did support the three-

year ban on taking action, as this time would be used to collect more information as to the

effects of smoking. A conference committee in Congress hammered out a bill that contained a

four-year ban. President Johnson's signature made the bill law on 27 July 1965 as the Federal

Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act of 1965 (FCLAA).

With research and reports continuing to show the same link as before, the FCC was the first to

take further action when it ruled on cigarette advertising. The ruling stated that anti-smoking

Public Service Announcements (PSA) with a specific ratio of one PSA for every three

commercials must be shown. The television stations were not happy with this arrangement and

showed the PSAs as part of their late-night programming. To combat this, the government

mandated, according to "Butt Out: The Life and Death of Cigarette Advertising on TV," that the

PSA's must be shown during prime time television. More action was needed to save lives.

The deathnell for tobacco advertisements came with the Public Health Cigarette

Smoking Act of 1969 (PHCSA). The FCLAA was only a temporary solution and was about to

expire. The PHCSA was the necessary step against the proliferation of advertising on television

and radio. The Act was brought about, in part, by another report released by the Surgeon

General's office in the same year and continued pressure by public health advocates. The

report linked "cigarette smoking to low birth weight." The legislation "required cigarette

manufacturers to place warning labels on their products that stated "Cigarette Smoking May

be Hazardous to Your Health." Even though there was a raging battle between the interests of

both the tobacco and public health lobbyists, Congress was forced into action.

Television and radio stations were not pleased with the situation because a large portion

of their annual revenue was derived from cigarette advertising. Despite pressure from various

forces, President Richard Nixon signed the Act into law on 1 April 1970. The ban was now law,

but in a compromise with tobacco-producing states, the ban would only take effect on 2

January 1971. The compromise allowed ads to be run during the college football games, a

New Year's Day tradition that draws in millions of viewers from across the United States. An era

came to an end with the final advertisement being shown on New Year's Day at 11:50 pm in the

middle of the American television institution that was "The Johnny Carson Show." The ad was

for a brand that targeted women, Virginia Slims. The PHCSA changed the advertising

landscape in the United States. It helped remove the perpetual onslaught of advertisements

that were found to be influencing children who needed to be protected in order to bring down

the rates of future smokers.

The special interest affected by the law filed lawsuits to block the law from taking effect.

One of these was Capital Broadcasting Company v Mitchell of 1971. The premise of the suit

was that section 6 of the Act violated the company's First Amendment right to free speech.

Capital Broadcasting lost as a federal district court stated in its decision that "product

advertising is less vigorously protected than other forms of speech." The Supreme Court

brought the suit to a permanent end when the court "denied certiorari. Certiorari is a legal term

whose definition is as follows, ...

"Certiorari allows higher courts, such as the Supreme Court, to review and correct lower court

decisions. It focuses on significant legal questions with broader implications, enabling

appellate courts to prioritize cases that shape precedents and ensure consistent application of

the law. The discretionary nature of certiorari means that courts choose only cases with

substantial impact, such as those involving conflicting rulings across jurisdictions or unresolved

federal questions. For example, the U.S. Supreme Court grants certiorari to only about 1-2% of

the thousands of petitions filed annually, underscoring its selective use."

The PHCSA was not the end-all, be-all of governmental regulation concerning the

tobacco industry. Still, it was a step in the right direction. Much more legislation and court

cases would follow in the decades to come. The long battle to bring down the number of

smokers, thereby reducing the amount of death caused by cigarettes has paid off to an extent.

However, the struggle between big tobacco and public health advocates still rages as

companies continue to push their products and the misinformation surrounding them, and

health advocates release factual information in order to combat the misinformation. There is no

foreseeable end in sight.

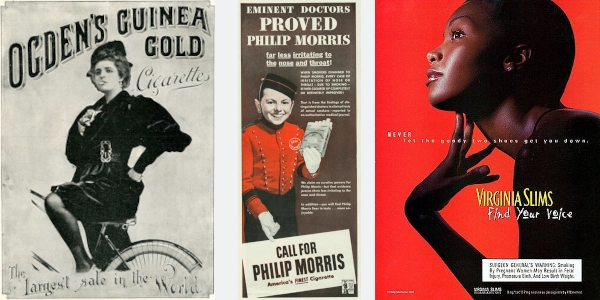

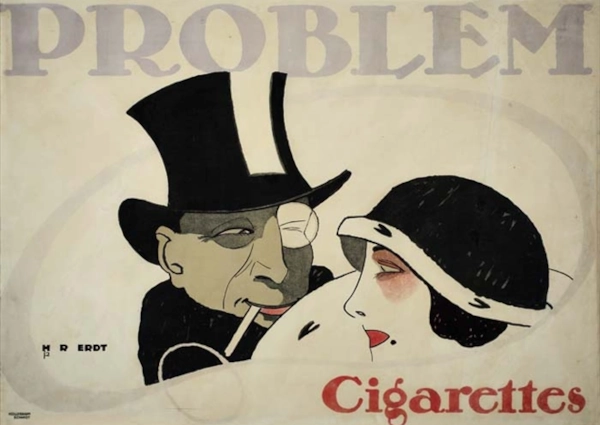

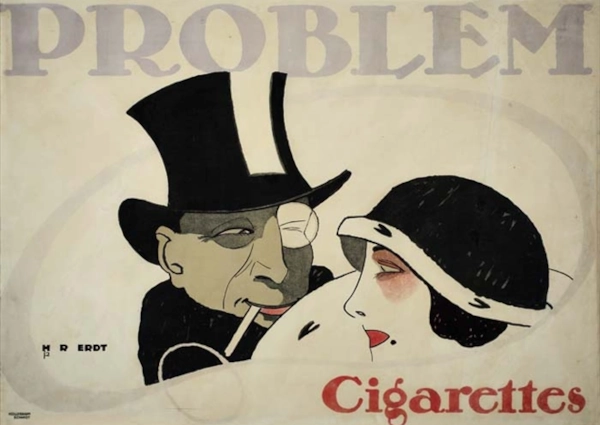

Photo above: Cigarette ad from 1912 for Problem Cigarettes, 1912, Hans Rudi Erdt. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons. Photo below: Montage: (left) 1900 Advertisement for Ogden's Guinea Gold Cigarettes, 1900, Ogden and Phillip's; (center) 1943 Advertising for Philip Morris, 1943, Philip Morris Tobacco; (right) 1999 advertisement for Virginia Slims, 1999, Philip Morris. All courtesy Wikipedia Commons.Future hotels built at Disney World, the Swam and Dolphin, 2007, Carol M. Highsmith. Courtesy Library of Congress. Source info: "Butt Out: The Life and Death of Cigarette Advertising on TV." www.youtube.com; Brown Baker, Nina. Reader's Digest 2019, Picturesque Speech, 44-Word Power, 103-Laughter, 112-Index. Vol. 163; Sa, Charles, and Roy Peel. U. S. DEPARTMENT of COMMERCE, "Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act · the Legislation." Acsc.lib.udel.edu; "Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act of 1969 (1969)." The Free Speech Center; HISTORY.com Editors. "President Nixon Signs Legislation Banning Cigarette Ads on TV and Radio | April 1, 1970 | HISTORY." 2009.