Sponsor this page. Your banner or text ad can fill the space above.

Click here to Sponsor the page and how to reserve your ad.

-

Timeline

1630 Detail

February 20/22, 1630 - Myth of popcorn introduction to Pilgrim colonists at Plymouth by Indian Quadequine(a) begins.

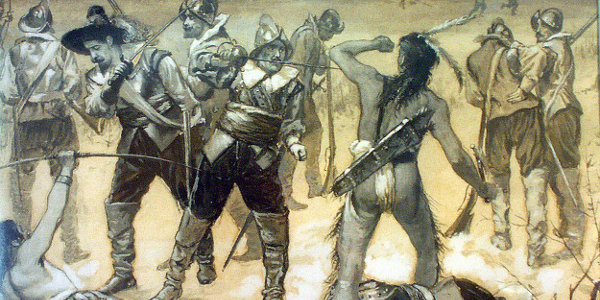

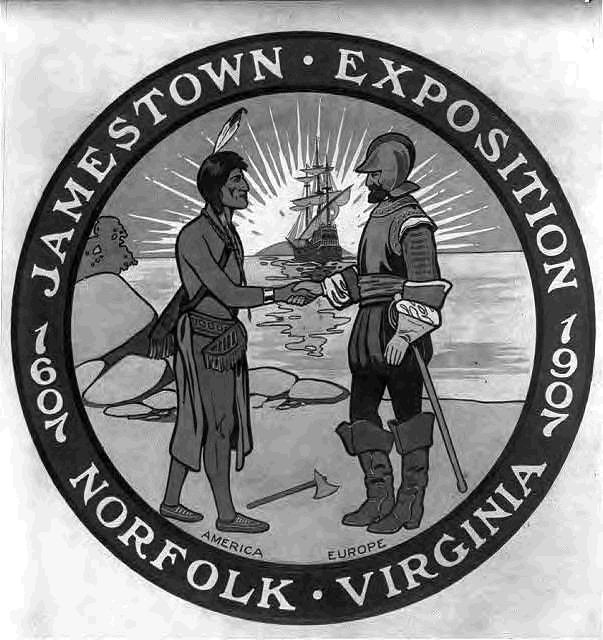

So how true is this story? Where did it come from? Was the date actually February 20 or 22 as some sources note. Has there been an investigation into the history of popcorn that can trace back to the Native Americans who roamed New England and the Plymouth Colony? Well, let's go back to geneology for a bit. A man named Quadequina Wampanoag existed, part of the Wampanoag tribe who lived in southeast Massachusetts and Rhode Island. They had been living on the land there for twelve thousand years. When the English came in 1620, there were sixty-seven villages of the tribe and forty thousand tribe members. Quadequina was among them, born around 1581, and lived til near 1661. Therefore, we can assume, that he was there during the beginning of the myth, or truth. He was the brother of their chief, Massasoit, and some records note the dates of Quadequina as those of his brother. The Wampanoag were a sedentary tribe with less nomadic tendencies than others. They liked where they lived. Unfortunately disease, and later in 1675, King Philip's War, eradicated much of that.

The Writer's Almanac contains the following excerpt ...

On February 22 in 1630, Quadequine, brother of Massasoit, leader of the Wampanoag tribe, introduced popcorn to the English colonists. He offered the treat as a token of goodwill during peace negotiations. The colonists called it popped corn, parching corn, or rice corn, and it was popped on top of heated stones or by placing the kernels, or cobs, into the hot embers of a fire."

Some question whether popcorn was served at the first Thanksgiving in 1621. It is not thought so, as the type of corn planted and harvested by the Wampanoag was not good for popping. In upstate New York, the Iroquois had better corn for popping. Somehow, perhaps, over the next nine years, there may have been some seed trading.

History of Popcorn

So while in American history, the myth, or truth, of the offering of popcorn to settlers in New England in 1630 is a nice story of European settlers and a peace offering by the Wampanoag, it's history is much older. Try four thousand years ago. A discovery in New Mexico bat caves found ears there in 1948-1950 which dated back to B.C. So, it is likely that popcorn, and corn itself, was an American thing. Yes, the Bible notes corn, but that may have been barley; the English corn was wheat, and the Irish corn was oats. Maize, i.e. American corn, is what is known today as corn. In South America, corn for popping was found in burial grounds of Northern Chile; it was one thousand years old and could still pop.

Upon European integration into Mexico and South America, Spaniard Bernardino de Sahugan, in the early 16th century, noted of the Aztecs...

"And also a number of young women danced, having so vowed, a popcorn dance. As thick as tassels of maize were their popcorn garlands. And these they placed upon (the girls') heads."

The instances of the Spanish encountering popcorn includes Explorer Cortes in 1519, and Spaniard Bernabé Cobo around 1659 in Peru where the Native Americans popped corn they called pisancalla. Of course today, popcorn is used as a snack, in movie theaters and home. Ella Kellogg ate it for breakfast with milk and cream. From 1890 to the Great Depression, street vendors would sell bags of the confection for 5 to 10 cents. They were a staple of local to world's fairs. First mobile popcorn machine was introduced by Charles Cretors at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. In World War II, a shortage of sugar in the United States (it was shipped to troops overseas) caused a three times more popcorn consumption. What about today? Americans eat 14 billion quarts of popcorn per year.

Minute Walk in History

Popcorn History

Watch a visual video of the history of popcorn as it made its way from four thousand years ago in Mexico to the first Europeans tasting it at Plymouth Colony (but not at the first Thanksgiving), through popcorn stands at local to world's fair, at the concession stands of drive-in movie theaters, to the treat on your couch.

Wampanoag Tribe

So what happened to the Wampanoag Tribe, also known as the People of the First Light? The Plymouth Colony was established in 1620 on Wampanoag land. Despite years of peace, followed by periods of war, the break between the Europeans and the Natives of the area broke with King Philip's War. After a European victory that cost many, some say more, deaths than any other Native vs. Settler war, forty percent of the Wampanoag were dead. Those left were often sold off as slaves. The remaining tribe members were given a deed to twenty-five square miles of land by the Plymouth Colony, although over the years, they took back more and more control. The King of England, however, agreed with the Wampanoag in 1760, that they should rule their own land.

However, with the battles of the American Revolution on the horizon, dynamics were about to change. Crispus Attucks, the first man killed in the American Revolution, was a Wampanoag and the Mashpee fought on the side of the people for independence. However, despite their assistance in establishing a new nation, their attempts to remain a recognized tribe, Mashpee, was essentially extinguished in 1870, even though it was against the 1790 Trade and Intercourse Act. It took until 1976 that one of their tribes, the Mashpee Wampanoag, took their land claims to federal court.

Of the original sixty-nine tribes of the Wampanoag nation, only three remain today with up to five thousand members, including the Mashpee. They were officially recognized in 2007 as the Washpee Wampanoag tribe with a three hundred and twenty acre reservation near Mashpee and Taunton. There are three thousand two hundred members of the Mashpee Tribe. Another tribe of the Wampanoag, the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head has 1,364 citizens. The third tribe is not federally, but state-recognized, Herring Pond. No citizen count is available.

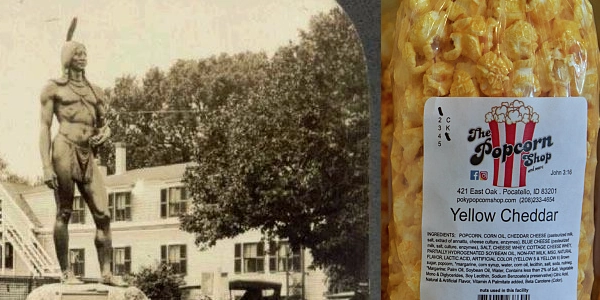

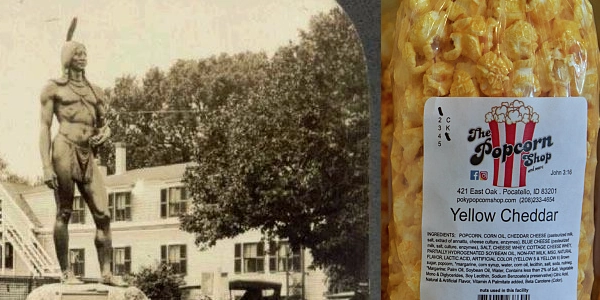

Source: Photo above: Montage left) Statue of Chief Massasoit of the Wampanoag tribe, brother of Quadequina, unknown date or photographer, Wikitree; (right) Current bag of popcorn at a shop in Pocatello, Idaho, 2022, Carol M. Highsmith. Courtesy Library of Congress. Image below: Popcorn stand at Gonzales, Texas County Fair, 1939, Russell Lee. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info source: The Writer's Almanac, 2021; "Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe," mashpeewampanoagtribe-nsn.gov; "Who are the Wampanoag," Nancy Eldridge, plimoth.org; Wikipedia; "The History of Popcorn and Thanksgiving," docpopcorn.com; "Popcorn: From Native Treat to Cinema Snack," sciteachonline.com; "History of Popcorn," popcorn.org.

History Photo Bomb

The Writer's Almanac contains the following excerpt ...

Some question whether popcorn was served at the first Thanksgiving in 1621. It is not thought so, as the type of corn planted and harvested by the Wampanoag was not good for popping. In upstate New York, the Iroquois had better corn for popping. Somehow, perhaps, over the next nine years, there may have been some seed trading.

History of Popcorn

So while in American history, the myth, or truth, of the offering of popcorn to settlers in New England in 1630 is a nice story of European settlers and a peace offering by the Wampanoag, it's history is much older. Try four thousand years ago. A discovery in New Mexico bat caves found ears there in 1948-1950 which dated back to B.C. So, it is likely that popcorn, and corn itself, was an American thing. Yes, the Bible notes corn, but that may have been barley; the English corn was wheat, and the Irish corn was oats. Maize, i.e. American corn, is what is known today as corn. In South America, corn for popping was found in burial grounds of Northern Chile; it was one thousand years old and could still pop.

Upon European integration into Mexico and South America, Spaniard Bernardino de Sahugan, in the early 16th century, noted of the Aztecs...

"And also a number of young women danced, having so vowed, a popcorn dance. As thick as tassels of maize were their popcorn garlands. And these they placed upon (the girls') heads."

The instances of the Spanish encountering popcorn includes Explorer Cortes in 1519, and Spaniard Bernabé Cobo around 1659 in Peru where the Native Americans popped corn they called pisancalla. Of course today, popcorn is used as a snack, in movie theaters and home. Ella Kellogg ate it for breakfast with milk and cream. From 1890 to the Great Depression, street vendors would sell bags of the confection for 5 to 10 cents. They were a staple of local to world's fairs. First mobile popcorn machine was introduced by Charles Cretors at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. In World War II, a shortage of sugar in the United States (it was shipped to troops overseas) caused a three times more popcorn consumption. What about today? Americans eat 14 billion quarts of popcorn per year.

Minute Walk in History

Popcorn History

Watch a visual video of the history of popcorn as it made its way from four thousand years ago in Mexico to the first Europeans tasting it at Plymouth Colony (but not at the first Thanksgiving), through popcorn stands at local to world's fair, at the concession stands of drive-in movie theaters, to the treat on your couch.

Wampanoag Tribe

So what happened to the Wampanoag Tribe, also known as the People of the First Light? The Plymouth Colony was established in 1620 on Wampanoag land. Despite years of peace, followed by periods of war, the break between the Europeans and the Natives of the area broke with King Philip's War. After a European victory that cost many, some say more, deaths than any other Native vs. Settler war, forty percent of the Wampanoag were dead. Those left were often sold off as slaves. The remaining tribe members were given a deed to twenty-five square miles of land by the Plymouth Colony, although over the years, they took back more and more control. The King of England, however, agreed with the Wampanoag in 1760, that they should rule their own land.

However, with the battles of the American Revolution on the horizon, dynamics were about to change. Crispus Attucks, the first man killed in the American Revolution, was a Wampanoag and the Mashpee fought on the side of the people for independence. However, despite their assistance in establishing a new nation, their attempts to remain a recognized tribe, Mashpee, was essentially extinguished in 1870, even though it was against the 1790 Trade and Intercourse Act. It took until 1976 that one of their tribes, the Mashpee Wampanoag, took their land claims to federal court.

Of the original sixty-nine tribes of the Wampanoag nation, only three remain today with up to five thousand members, including the Mashpee. They were officially recognized in 2007 as the Washpee Wampanoag tribe with a three hundred and twenty acre reservation near Mashpee and Taunton. There are three thousand two hundred members of the Mashpee Tribe. Another tribe of the Wampanoag, the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head has 1,364 citizens. The third tribe is not federally, but state-recognized, Herring Pond. No citizen count is available.

Source: Photo above: Montage left) Statue of Chief Massasoit of the Wampanoag tribe, brother of Quadequina, unknown date or photographer, Wikitree; (right) Current bag of popcorn at a shop in Pocatello, Idaho, 2022, Carol M. Highsmith. Courtesy Library of Congress. Image below: Popcorn stand at Gonzales, Texas County Fair, 1939, Russell Lee. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info source: The Writer's Almanac, 2021; "Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe," mashpeewampanoagtribe-nsn.gov; "Who are the Wampanoag," Nancy Eldridge, plimoth.org; Wikipedia; "The History of Popcorn and Thanksgiving," docpopcorn.com; "Popcorn: From Native Treat to Cinema Snack," sciteachonline.com; "History of Popcorn," popcorn.org.

History Photo Bomb

Wampanoag Tribe

So what happened to the Wampanoag Tribe, also known as the People of the First Light? The Plymouth Colony was established in 1620 on Wampanoag land. Despite years of peace, followed by periods of war, the break between the Europeans and the Natives of the area broke with King Philip's War. After a European victory that cost many, some say more, deaths than any other Native vs. Settler war, forty percent of the Wampanoag were dead. Those left were often sold off as slaves. The remaining tribe members were given a deed to twenty-five square miles of land by the Plymouth Colony, although over the years, they took back more and more control. The King of England, however, agreed with the Wampanoag in 1760, that they should rule their own land.

However, with the battles of the American Revolution on the horizon, dynamics were about to change. Crispus Attucks, the first man killed in the American Revolution, was a Wampanoag and the Mashpee fought on the side of the people for independence. However, despite their assistance in establishing a new nation, their attempts to remain a recognized tribe, Mashpee, was essentially extinguished in 1870, even though it was against the 1790 Trade and Intercourse Act. It took until 1976 that one of their tribes, the Mashpee Wampanoag, took their land claims to federal court.

Of the original sixty-nine tribes of the Wampanoag nation, only three remain today with up to five thousand members, including the Mashpee. They were officially recognized in 2007 as the Washpee Wampanoag tribe with a three hundred and twenty acre reservation near Mashpee and Taunton. There are three thousand two hundred members of the Mashpee Tribe. Another tribe of the Wampanoag, the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head has 1,364 citizens. The third tribe is not federally, but state-recognized, Herring Pond. No citizen count is available.

Source: Photo above: Montage left) Statue of Chief Massasoit of the Wampanoag tribe, brother of Quadequina, unknown date or photographer, Wikitree; (right) Current bag of popcorn at a shop in Pocatello, Idaho, 2022, Carol M. Highsmith. Courtesy Library of Congress. Image below: Popcorn stand at Gonzales, Texas County Fair, 1939, Russell Lee. Courtesy Library of Congress. Info source: The Writer's Almanac, 2021; "Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe," mashpeewampanoagtribe-nsn.gov; "Who are the Wampanoag," Nancy Eldridge, plimoth.org; Wikipedia; "The History of Popcorn and Thanksgiving," docpopcorn.com; "Popcorn: From Native Treat to Cinema Snack," sciteachonline.com; "History of Popcorn," popcorn.org.